Ambition and adventure: the early life of Arthur Phillip

In 2014 - the bicentenary of Arthur Phillip’s death - we looked back at the early life of this intriguing man, who had enjoyed an extraordinary career before he even set foot on a boat bound for Botany Bay.

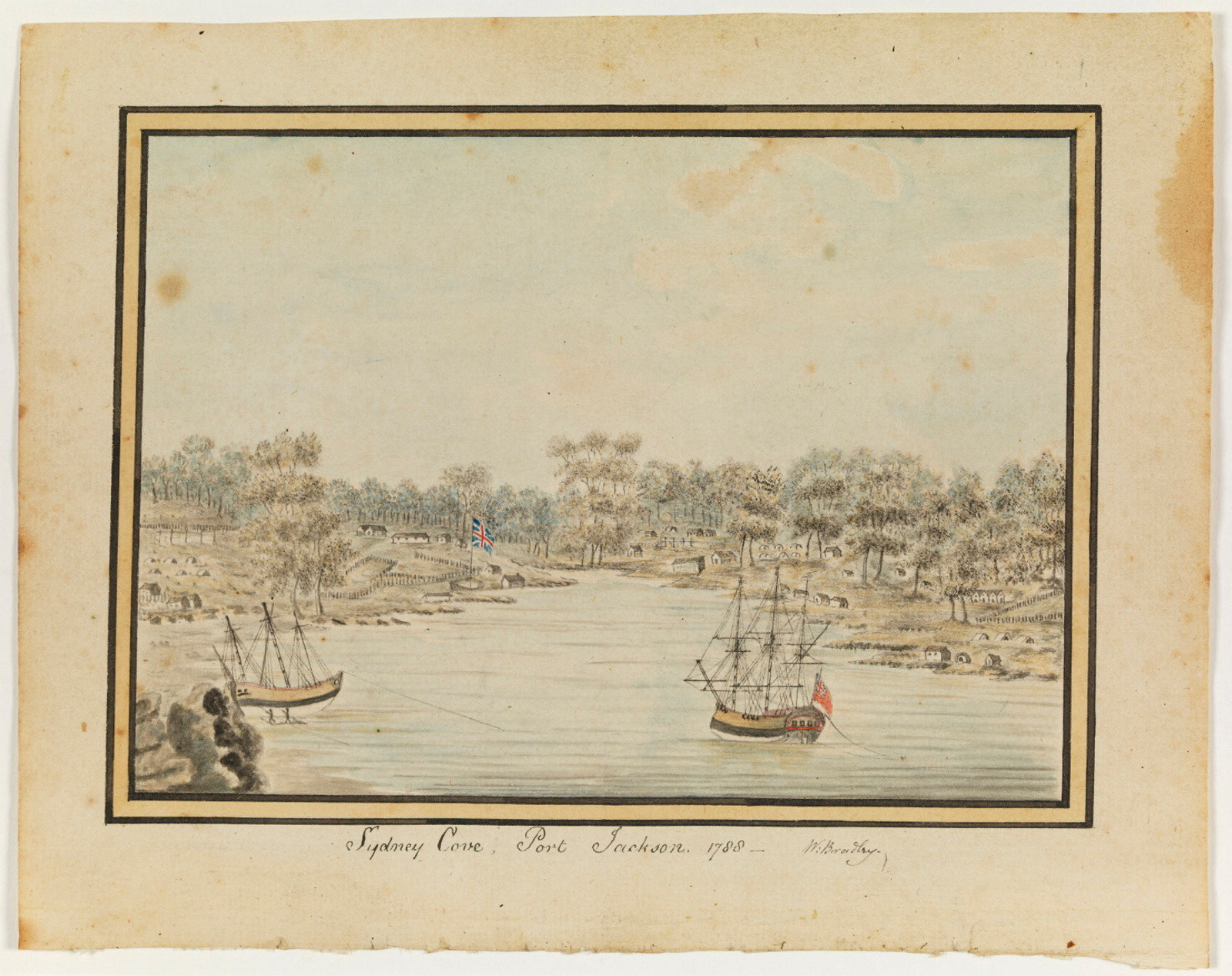

As dawn broke on 13 May 1787, Governor Arthur Phillip (1738–1814) gave the signal to weigh anchor, and the 11 ships assembled at Portsmouth – carrying 1500 convicts, officers and marines – set sail on a remarkable journey to the ends of the earth.

There is no doubt this historic voyage of the First Fleet and the founding of the NSW colony are significant achievements. But Arthur Phillip’s often-overlooked early life and career shaped his time as governor and deserve far more of our attention.

His is a story of ambition and determination against the odds. In an age when wealth, class and patronage ruled, he came from a humble family without land or influence. Naval advancement for those without connections depended on military engagements, but for many years in times of peace Phillip had to support himself as a lieutenant on half-pay. His first marriage to a wealthy widow brought him landed estates and respect as a gentleman, but the union was short-lived and Phillip returned all property to his estranged wife.

In spite of it all, Phillip built a remarkable career for himself. Whaling in the Arctic Ocean, trading in the Mediterranean, fighting in the Seven Years War and commanding Portuguese naval squadrons, not to mention espionage in France – his was a life of adventure, yet tempered always by his meticulous personality and strict moral compass.

Early life at sea

Phillip was born on 11 October 1738 in the parish of All Hallows, Bread Street ward, London, the second child of Jacob Phillip and his wife, Elizabeth. From the age of 12 he was educated for a life at sea at the Royal Hospital School at Greenwich, and three years later was apprenticed on the 210-ton whaling and trading vessel Fortune, experiencing privations and harsh conditions on voyages to the Arctic Circle.

Cutting short his apprenticeship, Phillip joined the 70-gun ship HMS Buckingham just after his 17th birthday in 1755 as the Royal Navy prepared for war against France. The Seven Years War (1756–63) that followed was the first truly global conflict, and as ‘captain’s servant’, later promoted to fourth lieutenant, Phillip found himself at the heart of the action.

When Phillip returned to England at the end of the war he brought with him two things crucial to his later success: the experience of lieutenancy supervising a diverse crew, and the patronage of Captain Michael Everitt, a family connection, and Captain Augustus Hervey, who was a future politician and the third earl of Bristol.

Foreign service

By 1774 Phillip was 36 years old and eager for further promotion and a return to active service. On half-pay during peacetime, with his marriage to widow Charlott Denison over, Phillip at last found an opportunity to serve in the Portuguese Navy, supporting Britain’s ally in her conflict with Spain over colonial territory in South America. Endorsed by Captain Hervey, Phillip travelled to Lisbon, where the Portuguese king granted him a captain’s commission on 17 January 1775.

One of the officers of the most distinct merit that the Queen … has in her service in the Navy …1

Macquis do Lavradio, Viceroy of Brazil, May 1778

Between military engagements with the Spanish, Phillip, who was by now fluent in spoken and written Portuguese, spent time in Rio de Janeiro, strengthening his relationship with the Portuguese Viceroy of Brazil. The viceroy eventually gave him command of a captured Spanish warship the San Agustin. Phillip created detailed charts of Rio harbour and the Colonia coast, including one large chart that he carried with him when he returned to resupply at Rio harbour more than 10 years later with the First Fleet.

Secret service

Phillip returned to the Royal Navy in 1778, no doubt hoping to see active combat in the War of American Independence (1775–83). Instead, he served for several years along the English Channel and adjacent European coasts, steadily advancing from lieutenant, to master and commander, and to post captain by November 1781. But what comes next is something of a surprise.

In 1784 Phillip was engaged by the Home Office to investigate the French naval capacity at Toulon, his cover being that he needed leave from the Admiralty to travel to France ‘on Account of [his] private Affairs’. He was paid for two years of espionage work, reporting back on the escalating shipbuilding activities at French ports.

On 12 October 1786, a few months shy of completing his second year, Phillip received Lord Sydney’s commission for the governorship of NSW, the post for which he is best known but one that was far from his own ambitions of naval glory.

… a good man

His private papers long lost, we have come to know him best through the words of others, such as Colonel Landmann’s often-quoted description of Phillip as ‘the Gentleman the scholar and the seaman’3. We know him as a linguist fluent in five languages, a visionary determined to make the colony of NSW a future British asset and a moralist opposed to slavery. We know he was married twice and carefully nurtured a wide circle of patrons and connections in government and science.

Phillip navigated 11 ships to the other side of the world, where he determinedly met the challenge of establishing a new society in an unknown country. From the moment he stepped ashore at Botany Bay, Phillip’s character, vision, persistence and life experience enabled him to make thefledgling colony viable. And that’s no small feat for the man so often relegated to the first line of Australia’s history.

In 2014, we presented a range of activities to commemorate the death of Arthur Phillip, including a major symposium and daily tours.

Footnotes

1. Letter from the Macquis do Lavradio to Senhor Martinho de Mello e Castro, Rio de Janeiro, 10 May 1778. National Archives, Lisbon, reprinted in Louise Becke and Walter Jeffrey, The naval pioneers of Australia, John Murray, London, 1899, p319.

2. Horatio Nelson describing Phillip in a letter to his wife, 7 April 1798, private collection, quoted in Alan Frost, Arthur Phillip 1738–1814: his voyaging, Oxford University Press, 1987, p260.

3. Colonel George Landmann, Adventures and recollections of Colonel Landmann, Colburn & Co, London, 1852.

More stories

Browse all

First Fleet Ships

At the time of the First Fleet’s voyage there were some 12,000 British commercial and naval ships plying the world’s oceans

Convict Sydney

Convict punishment: the treadmill

As a punishment, convicts were made to step continuously on treadmills to power wheels that ground grain

Why were convicts transported to Australia?

Until 1782, English convicts were transported to America, however that all changed after 1783

Published on