Crooks like us

Imagine the human face as a theatre stage, across which stagger thoughts, feelings, moods and memories.

Or maybe think of it as a kind of ledger, a scrupulously kept record of suffering, joy, failure, health and illness. The face is also, so we believe, a register of moral states - we base some of our most abiding judgment s on the briefest of glances at the faces of others. And it is of course always a mirror.

Is there any mode of representation more simultaneously revealing and misleading than the photographic portrait? Does that split-second visual sampling capture something true about the subject, some fleeting aspect of the self hidden from normal view, or merely some random configuration of facial tics and twitches?

Let’s complicate it further: imagine that you’re a practised and expert liar who has broken the law and been caught out and now you're trying to save your skin. Or maybe you’re ready to make a clean breast of it and beg for mercy. Or maybe you're just playing the part of the penitent, but scheming all the while. Perhaps there's a mixture of fakery and genuine emotion there, playing themselves out.

Such are the potent circumstances surrounding the so-called ‘special photographs’ taken by Sydney police in the 1920s, discovered over recent years among the tens of thousands of negatives of the forensic photography archive at the Justice & Police Museum.

No documentation accompanies the images but we know that each portrait was taken in the aftermath of a crime and generally prior to the court appearance. Each portrait freezes a charged and fractious moment in an unfolding story.

These mysterious images are extraordinarily rich and engaging just as they are. But when we piece together the facts of each case, painstakingly gleaned from police and court records, newspaper reports and other sources, then a remarkable composite emerges: image and story catalyse one another in surprising ways. We find ourselves staring into the heart of human drama.

Crooks like us presented more than 200 stunningly reproduced images in delicate balance with their stories, creating a captivating relay between image and narrative, narrative and image. Look at the picture, read the story, then look at the picture again and see it anew.

Published on

Related

Browse all

Come in spinner!

Gambling in Australia is regulated by the state and some types of gambling are illegal. The game Two-up, with its catch cry of ‘Come in Spinner!’, is legal only on Anzac Day and only in some states

Museum stories

Gritty business

Immerse yourself in Sydney's chilling criminal past in this unique water-front museum of policing, law and disorder – with its grizzly collection of underworld weapons along with tales of mayhem and lawlessness, aptly described as an educational resource befitting a 'professor in crime'

Underworld

Behind the scenes: How to read a ‘special’

Around the world, police forces followed established conventions when taking mugshots. But Sydney police in the 1920s did things differently

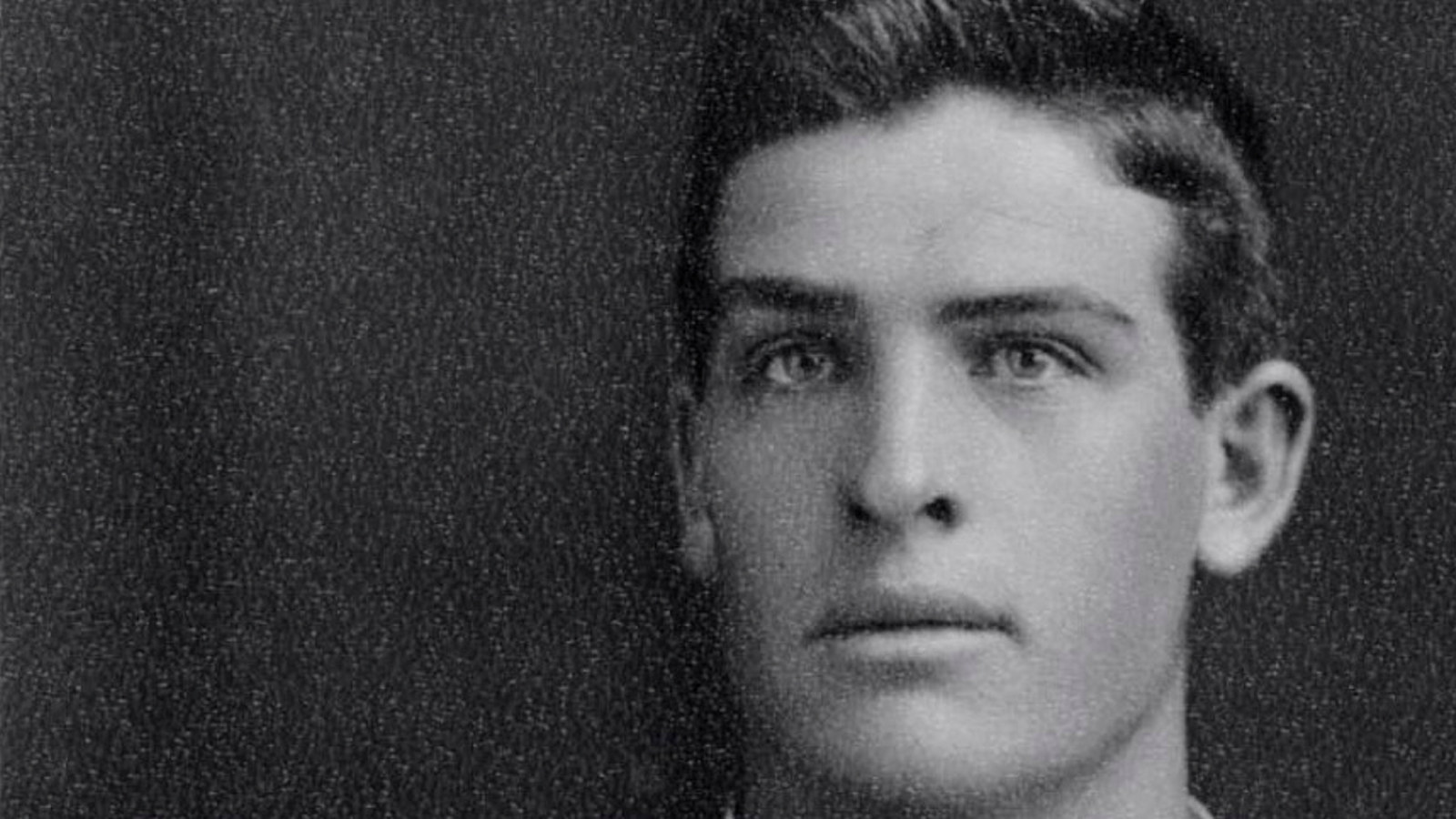

Police photographer George Howard

George B Howard was a prominent police photographer in Sydney during the 1920s