Talk of the town

To understand just how extraordinary a place Rouse Hill House is, first look around your own house or apartment.

Are you the first in your family to live there? Perhaps your parents or another relative lived there before you. Or is it an entirely new home? When you look around, do you see evidence of anyone who’s lived there before – perhaps furniture, perhaps a wall colour or wallpaper? When you look outside, are there trees that were planted many years before or is the landscaping new?

At Rouse Hill House six generations of the Rouse and Terry families occupied the house from its construction in the early 1800s until the late 1990s, when it opened as a museum. Each generation has left its mark, never erasing the evidence of those who lived there before but instead adding to it, forming a richly textured series of interiors and landscapes. Chairs from the 1840s sit beside textiles from the 1950s, grand tour paintings sit above mantelpieces crowded with photographs and mementos, and a 1960s television sits in a room whose walls were papered half a century earlier.

By a road, on a hill

Rouse Hill house was built because of a road: a ‘turnpike’, or toll road, built at the order of Governor Lachlan Macquarie. It replaced an earlier road made to reach the rich agricultural land discovered on the banks of the Hawkesbury. Richard Rouse, a free settler employed as the Superintendent of Public Works, was awarded the contract to build a tollhouse roughly half way between the colonial centres of Parramatta and Windsor near Second Ponds Creek, a reliable water source. He was then granted 450 acres (182 ha) of land beside the tollhouse, on the south side of the new road – verbally at first, then officially declared in 1816. Rather than a house he may have originally have intended to build an inn or coach house on the prominent, hilltop location.

On 27 November 1813, Governor Macquarie published a notice in the Sydney Gazette announcing a new toll on the Windsor Road:

THE New Road leading from Parramatta to Windsor, being some time since compleated and two Toll Gates erected thereon, with suitable Houses for the Accommodation of the Gate-Keepers, the Public are informed, that one of those Toll Gates is placed near to the Bridge over the River at Parramatta, and the other at Rouse Hill (some-times called Vinegar Hill), at a Distance of about eight Miles from Windsor; and Tolls will commence to be levied at those Gates, on the 1st Day of January next.

It was in this announcement that we read the name ‘Rouse Hill’ for the first time – and also the intriguing line ‘some-times called Vinegar Hill’. This records a darker side of the site’s history: a crushed convict uprising that took place there in 1804. Although ending a day after it began with the execution of its ringleaders, the uprising was the largest convict rebellion in Australian history. Led by a number of Irish political prisoners, the event was named after a battle that had taken place in Ireland in 1798 between the British Redcoats and Irish rebels.

Richard Rouse probably begun clearing, fencing and limited grazing at Rouse Hill around 1813. While the exact date the house was completed is unclear, in 1824 Richard, his wife Elizabeth and their family relocated there from Parramatta. Built from sandstone quarried near Parramatta, the house was an orderly, two-storey building, symmetrical inside and out, two rooms deep (or 'double-piled') with stables and a rear service wing. Originally the stark, severe façade featured the central entrance porch so familiar from other Macquarie-period houses in the Windsor-Richmond area, but this was replaced by a full verandah in the 1860s – a valuable concession to the climate – and a new two-storey service wing was built to the rear.

Living layers

Each generation to live at Rouse Hill made additions, improvements and adaptations. The second generation, Edwin and Hannah Rouse, extended the geometric grid of the first garden and planted notable trees, such as the now grand Moreton Bay figs. Widowed in 1862, Hannah also added the two-storeyed service wing. Third-generation Edwin Stephen and Bessie Rouse painted the house its distinctive ox-blood colour, added an internal bathroom. They also built new stables, which, designed by society architect John Horbury Hunt, epitomised the family's enduring interest in horses and horse breeding. As a wedding gift to Bessie and Stephen, Bessie’s father had the tall tank-stand beside the house installed, allowing the garden and Bessie’s delicate palms and ferns to be watered. Together with their children, Kathleen and Nina, and Nina’s husband George Terry, Edwin and Bessie took on the role of local squires, and by the 1890s Rouse Hill House had become a social and community hub.

The rear arcade, an enclosed area under a curved corrugated metal roof added between the two service wings, was the site of many a theatrical performance, amateur concert, charity fundraiser and wedding celebration. In 1895, the Rouse's hosted a lavish lunch for the Sydney Hunt Club, of which they were keen members, decking out the arcade with banners, flags and extravagent floral arrangements.

ROUSE HILL: Another Good Concert. On Friday night last the spacious Arcade at Rouse Hill House ... was filled to overflowing, and the entertainment proved an excellent one, quite as good as some of the best concerts held in Windsor … Mr Eric Terry, a good comedian, caused heaps of fun with his “sneezing song"...

Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 17 February, 1906

Hard times

By the fifth generation, the prosperity of the late 1800s was gone; severe drought and a banking crash had taken their toll. The family’s other estates, on which Rouse Hill depended, were sold. Nina and George’s five sons – Geoffrey, Roderick, Edwin (Ted), Gerald and Noel – divided the Rouse Hill estate, with Roderick and Gerald keeping the house and its immediate surrounds.

Yet it was this decline that ensured the remarkable preservation of the house, their belongings and the surrounding landscape; as little was moved or added, the interiors were preserved largely unchanged. By the 1970s the extraordinary nature of Rouse Hill was becoming recognised by historians and conservationists, and, through several open days, the wider community. Concerned that the house and its contents would be sold and dispersed, in 1978 the NSW government moved to resume the property, and progressively to acquire the contents, which had been divided between Gerald and his brother Roderick’s daughter Miriam. In 1986 the government transferred ownership of the estate to the recently formed Historic Houses Trust (now Museums of History NSW), which began the process of cataloguing over 20,000 items, while Gerald continued to live in one section of the house. During this time, the house was occasionally opened to the public, and following Gerald’s death in 1999, the house and farm opened as a dedicated museum. With the diverting of the Windsor Road in 2010, the museum site was enlarged to include the 1888 Rouse Hill schoolhouse, a section of the original Windsor Road laid down by Governor Macquarie in 1812, the site of the tollhouse and the area’s first watch-house, and a surviving pocket of Cumberland Plain woodland.

Today, as the surrounding suburbs press ever closer, the Rouse Hill Estate and adjoining regional park remain as one of the largest dedicated green spaces in the local area. Yet Rouse Hill is especially acknowledged for its intactness as a physical record of the everyday lives of a prominent colonial family over a 180-year period. It is a record that reflects the broader stories of the developing colony and city, of the Darug people whose land the farm now occupies, of new styles and technologies in architecture and design, farming and gardening, of changing tastes, fashions and times.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the house as a museum is the accumulation of physical traces of the lives lived within the rooms. Each generation of the family left their the mark, bringing their own touch to the decoration and furnishing of the house, demonstrating the tastes and fashions of their time, but leaving much of what already existed. The result is rooms that are complex and eclectic: in the sitting room, 1850s gilt curtain rods are hung with 1950s printed curtains, while chairs dating to 1860 have been kept and reupholstered multiple times, with the original textiles preserved like archaeological layers beneath more recent ones. Every shelf, cupboard and drawer is filled with items once owned by the family – books, letters and receipts, kitchen and dining ware, clothing, ornaments, loose buttons and bathroom products – everything a lived-in house would usually contain. Each item is kept for the story it tells about the lives lived here – no item, no matter how small, is insignificant. It is for this reason that Rouse Hill is an extraordinary physical archive for those wishing to find out about how people lived and worked in the past.

Visitors to Rouse Hill will often look upon an item and exclaim, ‘my grandmother had one of those!’ And quite possibly she did.

Published on

Related

A Gothic Angel

In the drawing room at Rouse Hill your eye is instantly drawn to a small painting on the far wall; a figure of an angel in a shining gilt frame, acquired in the 1870s.

Keeping cool

Shading the face, fanning a fire into a blaze or cooling food, shooing away insects, conveying social status, even passing discreet romantic messages - the use of the fan goes far beyond the creation of a breeze.

WW1

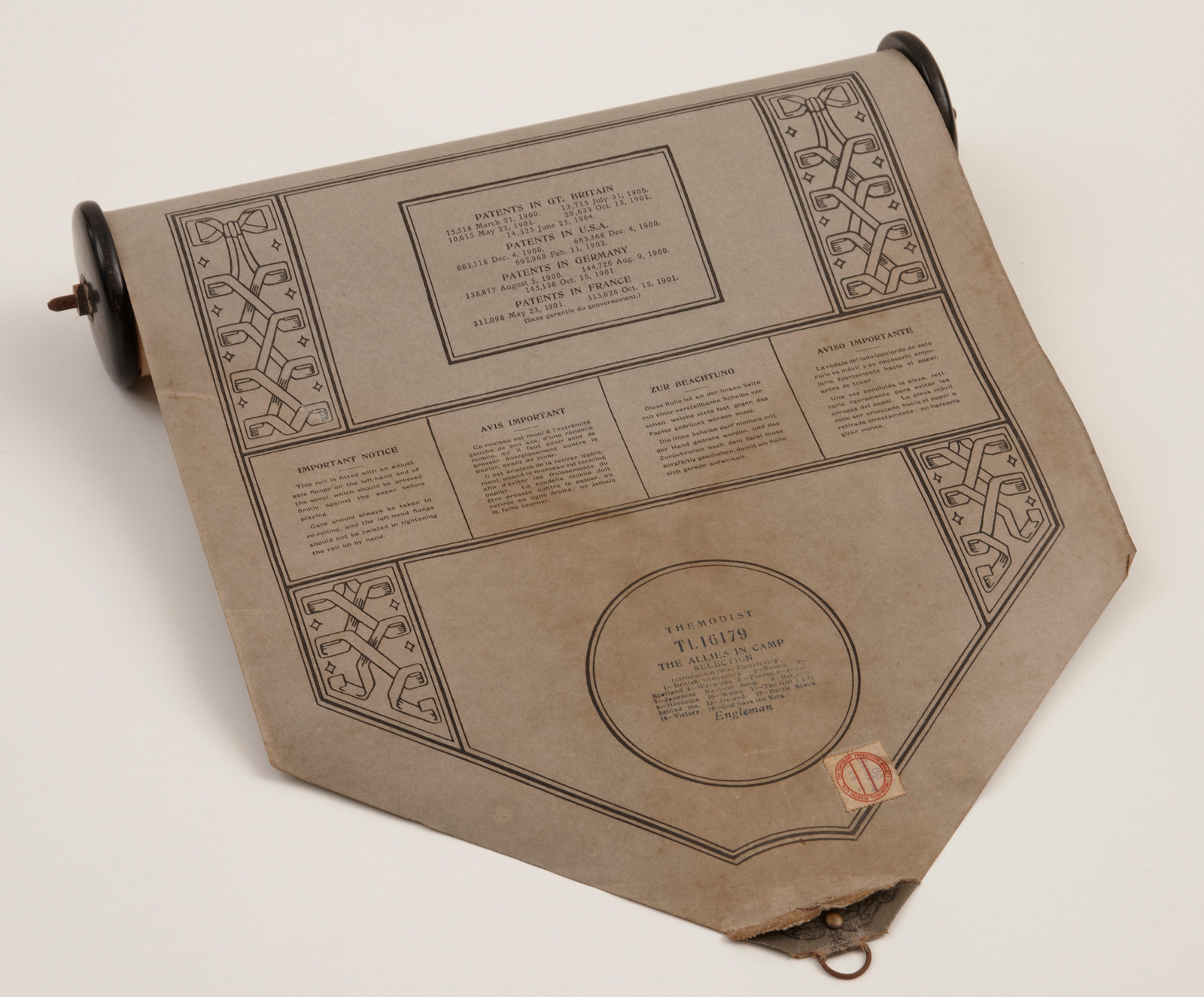

The Allies in camp music roll

Rouse Hill house boasts a fine pianola, a player piano, which came into the house just a few years before the outbreak of World War I