Stories

Our houses, museums and collections are packed to the brim with stories of all kinds

A look back at the Sydney 2000 Olympics

Do you remember when Olympic Fever hit Sydney in 2000? The Olympic Games and Paralympic Games in Sydney welcomed and hosted over 11,000 athletes from 199 countries. Together with 50,000 volunteers and millions of spectators Sydney captured the attention of the world - a city of sport, festivals, arts, community, friendship and fun

The Great White Fleet, 1908

On 20 August 1908 a round the world peace mission by the American fleet arrived in Port Jackson and marked the start of Fleet Week, a week-long celebration of events, parades and parties

‘The people’s house’: what’s in a name?

The ‘Sydney Opera House’, the ‘Opera House’, or simply ‘the House’ – we know it by many names. But why is this Australian icon also called ‘the people’s house’? Exhibition curator Dr Scott Hill explores the story behind a name

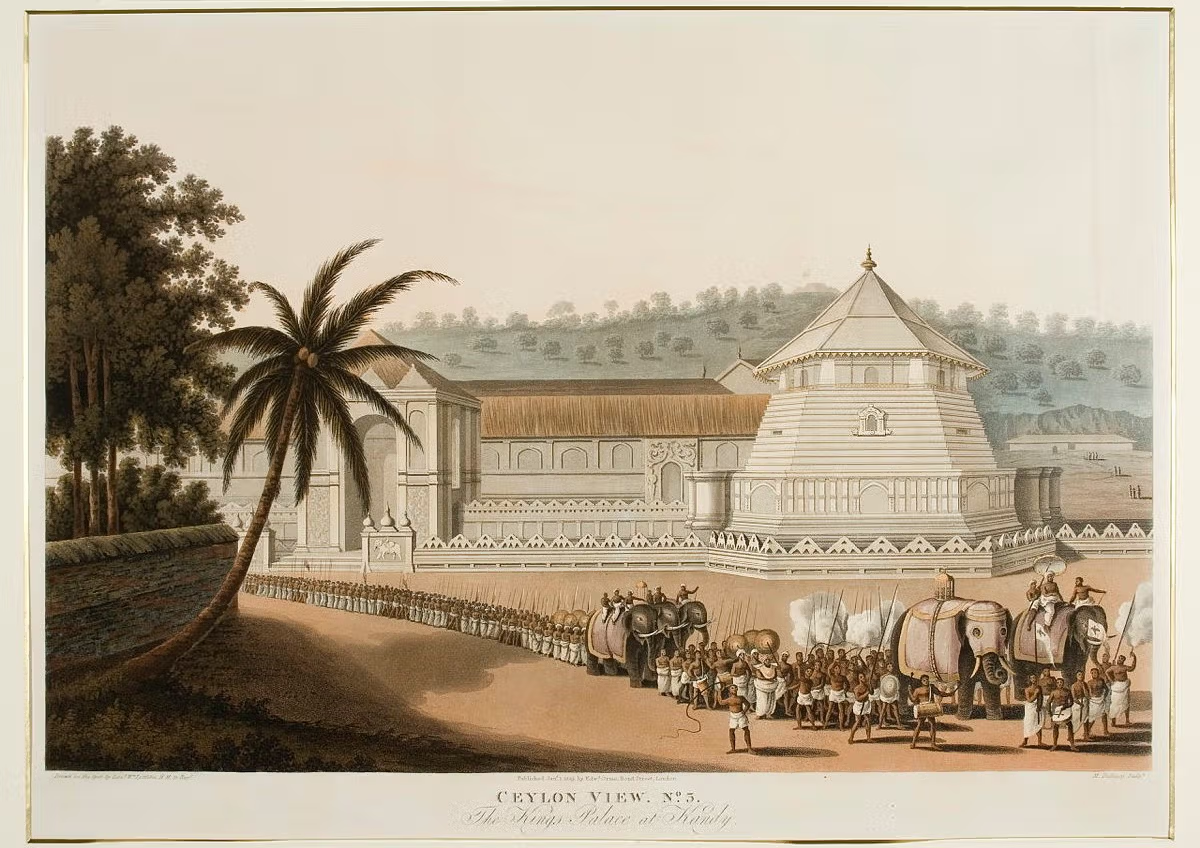

Collection insights from a guest refugee curator

Jagath Dheerasekara has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions and his work is held in both institutional and private collections across Australia

The coolest room in the house

What practical techniques can we learn from historical building design to minimise heat and energy consumption in our homes today?

Two Point Perspective: Enrico Taglietti, a facade of shadows

In this podcast our presenters Rebecca Hawcroft and Kieran McInerney go on the road to western NSW and Canberra to look at the work of an Italian architect

First Nations stories

Browse all

Cast in cast out: recasting fragments of memory

An in-depth look at Dennis Golding's experiences and childhood memories of growing up in ‘The Block’

First Nations

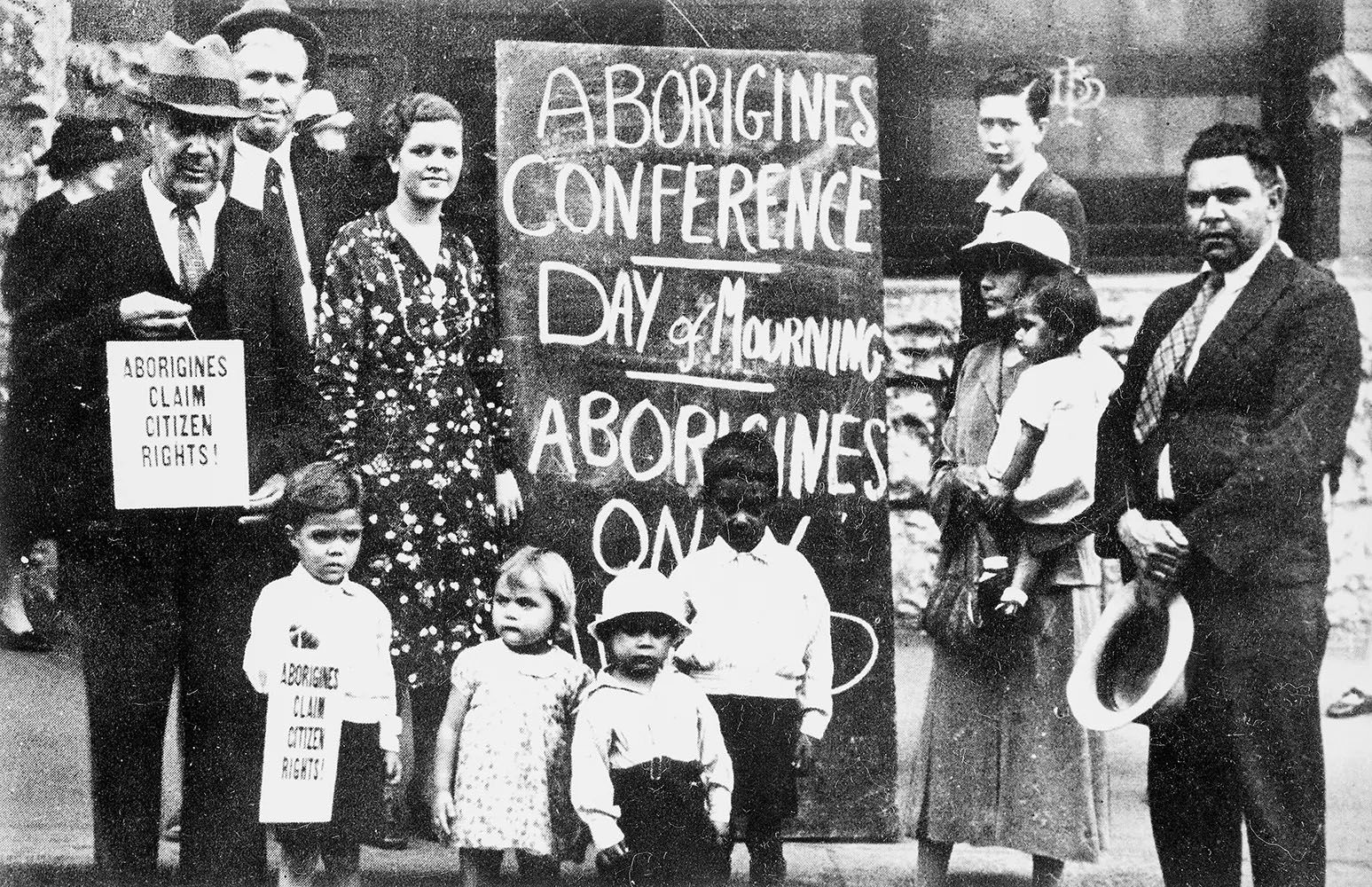

Day of Mourning

January 26 has long been a day of debate and civic action. Those who celebrate may be surprised of the date’s significance in NSW as a protest to the celebrations of the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet on what was then “Anniversary Day” in NSW

First Nations

How to weave an opera house

Inspired by a stunning shellworked model of the Sydney Opera House by Bidjigal artist Esme Timbery, First Nations curator Tess Allas commissioned a woven model of the iconic building from master weavers Steven Russell and Phyllis Stewart

Cutter and Coota: a children’s play by Bruce Pascoe

Meet author and historian Bruce Pascoe and the main characters from his play Cutter and Coota as they reflect on the play’s themes and the experience of performing at the Hyde Park Barracks

Convicts

Browse all

Convict Sydney

Convict Sydney

From a struggling convict encampment to a thriving Pacific seaport, a city takes shape.

Hyde Park Barracks – the convict years

In 1788, the penal colony of New South Wales was established on the Country of the Gadigal people

Convict Sydney

The turning tide

Amidst public outcry, the convict ships stop but the ‘stain’ of Sydney’s convict past is harder to erase

Convict Sydney

Objects

These convict-era objects and archaeological artefacts found at Hyde Park Barracks and The Mint (Rum Hospital) are among the rarest and most personal artefacts to have survived from Australia’s early convict period

Conservation

Browse all

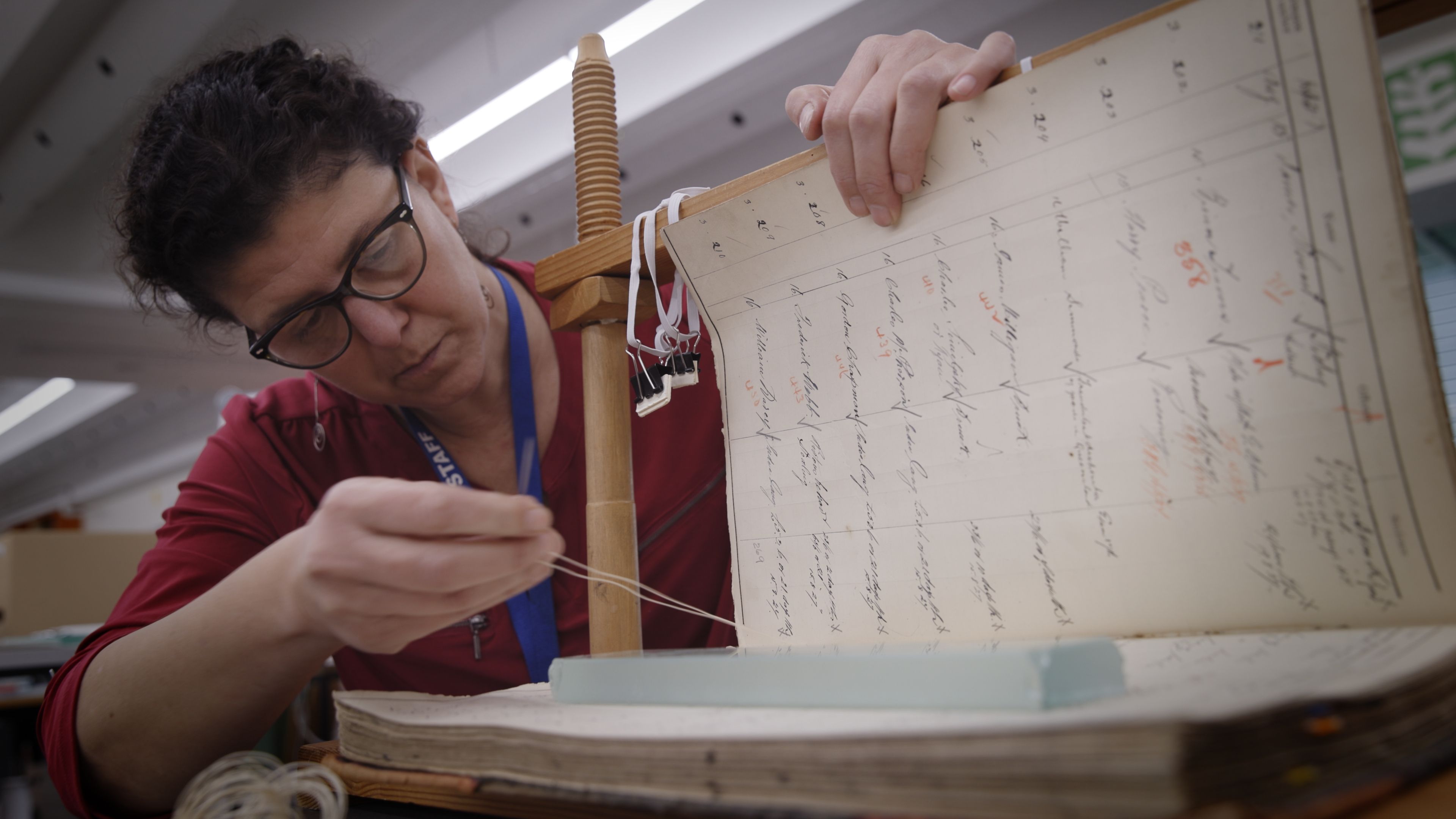

Conserving the archive

Supervising conservator Dominique Moussou talks through her work and some of the projects underway in the MHNSW conservation lab

Conservation

Susannah Place conservation project

A behind-the-scenes look at some of the complex work that goes into conserving and preserving the fascinating Susannah Place Museum

Conservation

A strong and simple structure: conserving the woolshed

The second phase of a major conservation project on the woolshed at Rouse Hill Estate has seen the rustic 160-year-old structure strengthened and stabilised

Conserving Harry Seidler’s sofa

A sofa Harry Seidler designed for Rose Seidler House was conserved and reupholstered, and the process revealed some unexpected findings

Stories about our places

Museum stories

A turbulent past

With its deep, shady verandahs and elegant symmetry, Elizabeth Farm is an iconic early colonial bungalow

Museum stories

Gritty business

Immerse yourself in Sydney's chilling criminal past in this unique water-front museum of policing, law and disorder – with its grizzly collection of underworld weapons along with tales of mayhem and lawlessness, aptly described as an educational resource befitting a 'professor in crime'

Museum stories

Make yourself at home

Meroogal became home to four generations of resilient and resourceful women, whose house was their livelihood as well as their home

Museum stories

Not a lovelier site

‘There is not a lovelier site in the known world’, wrote the Sydney-born barrister and novelist John Lang about the Wentworth family’s estate of Vaucluse

3D story telling

Browse all

'A most excellent brick house' Elizabeth Farm

Curator Dr Scott Hill explores some of the enduring mysteries buried in the architecture of Australia’s oldest surviving homestead

3D scanning the archaeological dog skeleton

A key component of Museum of Sydney’s interpretation is the archaeological remains of First Government House

Museum stories

A rum deal

When Lachlan Macquarie began his term as governor of NSW in 1810, Sydney was in desperate need of a new hospital

Plant your history

Browse all

Plant your history

Beautiful bountiful bamboo

One of the most recognisable plants growing at Museums of History NSW today is bamboo. This colourful plant has a long history in colonial gardens

In the pink at Elizabeth Farm

Amid the late summer bounty in the garden at Elizabeth Farm, the crepe myrtle is the undoubted star of the show

Plant your history

Sumptuous cape bulbs light up late summer gardens

Belladonna Lilies and Crinum Lilies are tough bulbs that never say die and can survive years of neglect

Plant your history

Acanthus - an apt symbol for The Mint

Look at any classical building today, anywhere in the world and chances are you will find an acanthus leaf lurking somewhere

Dodgy, dangerous, disturbing

3D models: a fascinating exploration of some seemingly innocent objects modified for nefarious purposes from the Justice & Police Museum collection

ExploreStay updated

Be the first to find out about our latest news, stories, events and more.

Sign up to eNews