Israel Chapman

Robber, policeman, robber again

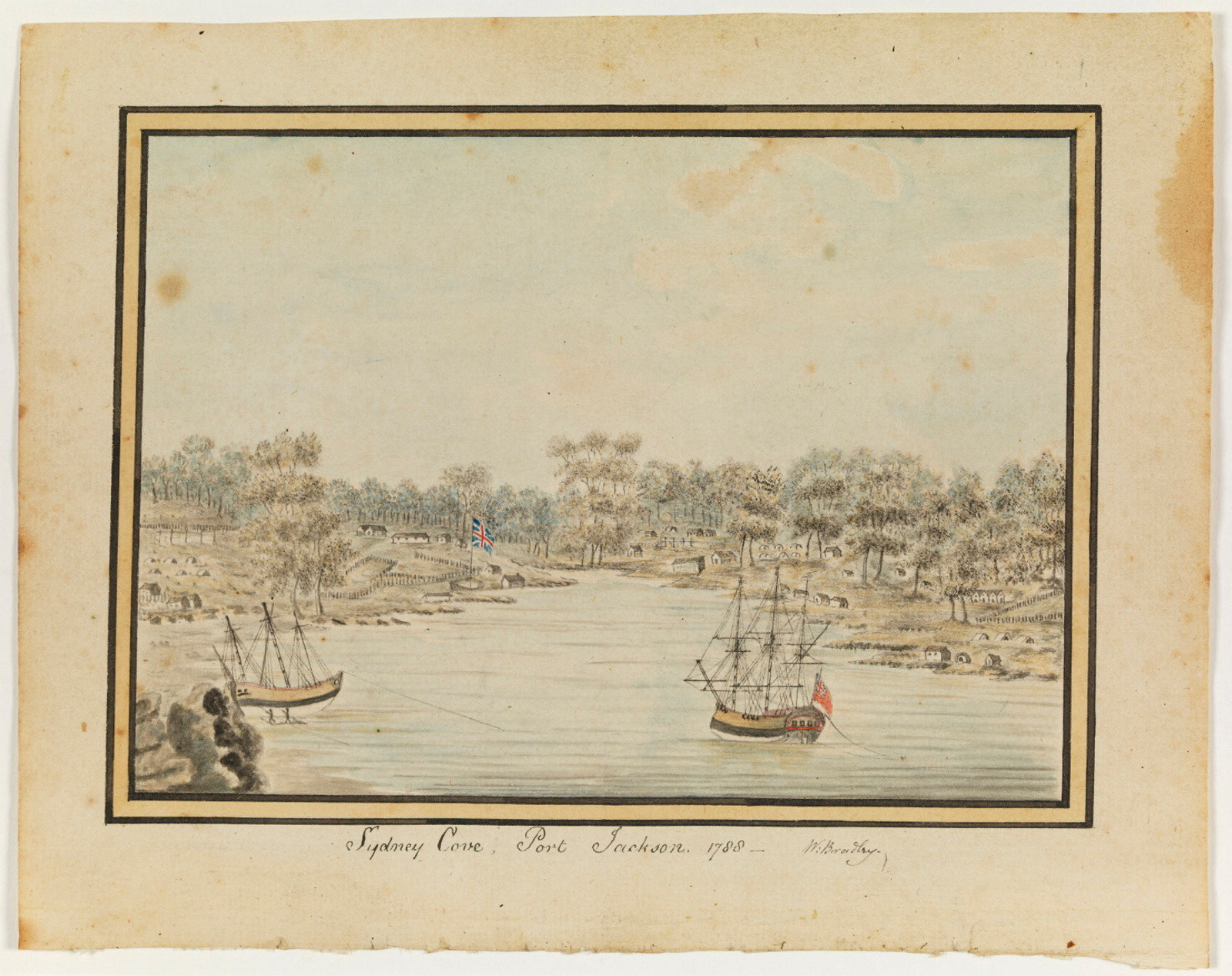

Arrived 1818 on Glory

Could a 24-year-old convicted armed robber be trusted to maintain law and order among hundreds of prisoners? Perhaps not, but that’s exactly the job Londoner Israel Chapman was given at Governor Macquarie’s newly opened Prisoners’ Barracks at Hyde Park in 1819.

Chapman was appointed to this responsible job from within the ranks of the convicts, maybe because he was the best of a bad bunch of untrustworthy men, or perhaps because of his influential, charismatic character and air of honesty.

Only two years before, Chapman was driving coaches, known as ‘rumble-tumbles’ and ‘rattlers’, in London, transporting the city’s wealthy folk to and fro. But with all that opulence around him, he fell into temptation – highway robbery, a crime known in the slang of London’s underworld flash community as ‘scamp’ or ‘toby’. He was ‘nibb’d’ (taken into custody), then convicted, or ‘done for a scamp’, in January 1818.

Bearing the burden of a life sentence, Chapman sailed to the colony on Glory, and very soon he was rubbing shoulders with a very different crowd – the convict rabble at the Hyde Park Barracks.

Dressed in the overseer’s uniform of blue jacket and trousers, Chapman had to maintain order among the 1000 or so convicts housed there that year. Rousing the ‘lags’ (convicts) out of their hammocks in the early mornings, as the yard bell sounded to announce another day of toil and brutality, might have been the most challenging part of his job. Or maybe it was enforcing the snuffing out of oil lamps of an evening, when the convicts were enjoying playing cards, telling tales, making straw hats, and smoking pipes. As an overseer, his fellow convicts probably called him a ‘square cove’ (honest man), but we might wonder if he ever accepted a bribe in the shadows.

Chapman seems to have proven his worth quickly: after only 18 months in the job he was promoted to principal overseer and constable at the lumberyard. Organising the work of gangs of skilled convict ‘mechanics’, Chapman would have needed to be a good leader with the ability to get the most out of them.

In his constable role, he even captured some burglars and bushrangers, and by 1821 he received a conditional pardon. He was free but had to stay in the colony, and he made the most of it. Joining the police, as a detective working out of the George Street office he travelled the colony’s dirt roads and battled the dense scrub, catching escaped convicts-turned-bushrangers. He even took a few gunshot wounds for the cause. As the old saying goes, it takes a thief to catch a thief.

For his good work, the Governor granted him an absolute pardon in 1827, and the newspapers sang his praises, but Chapman had become the enemy of the convict ‘flash’ community. Irish convict poet Francis Macnamara even featured him in one of his poems ‘standing on his head, in a river of melted boiling lead’. At least one convict seemed to love him, though – his wife, Catherine Martin, whom he had married at St Philip’s Church in 1820.

In the end, after all the accolades and captured bushrangers, Chapman slipped back into his old habits, and was charged with robbery and sentenced to six months’ hard labour. In 1868 he died in Liverpool Asylum. This man certainly knew both sides of the law.

This content was compiled for the Convict Sydney website from existing information such as SLM exhibition text and other researched material © Sydney Living Museums, 2017.

Published on

Convicts

Convict Sydney

Leg Iron Guard

A stunning example of an improvised handicraft, this leather ankle guard or ‘gaiter’ was made to protect a convict’s ankle from leg irons

Why were convicts transported to Australia?

Until 1782, English convicts were transported to America, however that all changed after 1783

Convict Sydney

1844 - Day in the life of a convict

Fraying at the edges, these were the Barracks’ darkest days with only the worst convicts remaining

Convict Sydney

1801 - Day in the life of a convict

In the young colony, there was no prisoner’s barrack - the bush and sea were the walls of the convicts’ prison