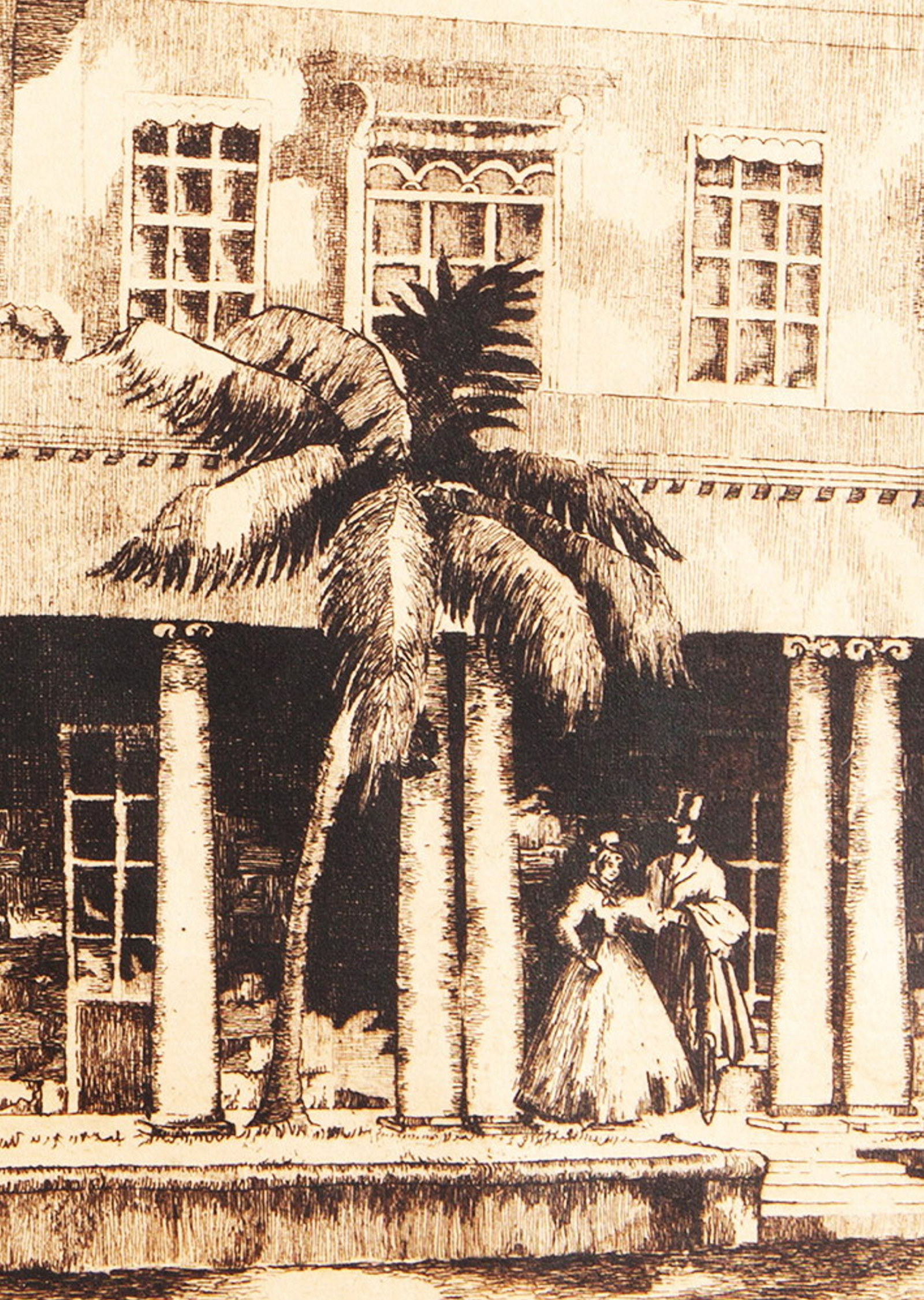

Burdekin House - St Malo columns

If the fluted timber columns made for Burdekin House now look a little battered and perhaps not as elegant as they were in the mid-19th century, it is hardly surprising after surviving two house demolitions.

Ten Greek-revival fluted columns with angular or ‘Scamozzi-style’ Ionic capitals were first made to adorn the front verandah of a grand house in Macquarie Street Sydney, built in 1841 for wealthy merchant Thomas Burdekin (1801-1844). When it was near completion in August 1841 the Sydney Herald pronounced it ‘the most handsome house in Sydney’, even suggesting that it would do discredit to no part of London.

The house remained in Burdekin family ownership and occupation until 1922 but barely a decade later it was demolished to make way for a new St Stephen’s Presbyterian Church. The church’s original building in Phillip Street had been resumed by the Sydney City Council for the extension of Martin Place through to Macquarie Street.

The historical significance of Burdekin House created a great deal of interest in the sale of its fixtures and fittings. Six of the ten timber verandah columns were acquired by Madame Rose Du Boise, a well-known figure in Sydney society. She used them, in a cut-down form, to replace the existing cast iron flat grille verandah columns on her c1856 house, St Malo, on the Lane Cove River at Hunters Hill.

In the late 1940s St Malo itself came under threat with plans to build an expressway through Hunters Hill and new bridges at Figtree and Gladesville. The National Trust of Australia (NSW) acquired a 20 year lease on St Malo in 1955 as part of a doomed campaign to save the property. The house was eventually demolished in 1960-61 and in 1961 the Burdekin House columns were again on the move, this time to the National Trust who found a new use for two of the columns later that same year: they took to the stage of the Old Courthouse theatre at Scone NSW. The remaining four, only one with a surviving capital and base, stayed with the National Trust until acquired by the Historic Houses Trust (now Museums of History NSW) for the Caroline Simpson Library in 2012.

Macquarie Street and Burdekin House, 1867-68

The design of Burdekin House has sometimes been attributed to a Scottish-born architect named James Hume (1804-1868) but in his survey of The early Australian architects and their work (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1954) architectural historian Morton Herman noted that there was also a tradition that the house was designed in London. Nonetheless he acknowledged that Hume was responsible for the architectural supervision of the construction and that the house was ‘superbly built and beautifully finished’ making it ‘the finest building in the Regency style in New South Wales’.

Thomas Burdekin lived to enjoy his house for only a brief few years before his death in 1844. The house then passed first to his wife, Mary Ann, nee Bossley (1806–1889), and later to his son, Sydney Burdekin (1839-1899), a city councillor, Lord Mayor of Sydney from 1890-1891 and member of the NSW Legislative Assembly from 1884 to 1894. The drawing room of Burdekin House was often used as a substitute venue for parliamentary party meetings.

Burdekin House, 1870s

Burdekin House was built with three storeys plus a basement as the land sloped away at the back of the house. As originally built in 1841 the house was 70 feet wide on the ground floor, extending across seven bays, with but only 55 feet wide on the upper floors, extending across 5 bays The end bays on the ground floor related to narrow galleries running the depth of the house. Wings were added above those bay on either side of the house, probably in the 1880s, by architect Oswald Hoddle Lewis (1833-1895), youngest son of NSW colonial architect Mortimer Lewis. O.H. Lewis also designed a billiard room, which adjoined the house but had a separate entrance. He was the architect of choice for the Burdekin family’s vast property portfolio over many years.

Drawing room at Burdekin House, c1905

The drawing room at Burdekin House was a notable space for entertaining in the 19th century. It ran the full depth of the house, 40 feet 5 inches (12.3 metres) and was noted for its elaborate Louis-revival interior, the walls richly decorated with rococo moulded plaster ornament. Most notable were the extravagantly painted ceilings and walls, white onyx fireplaces and over-mantels with painted cherubs. Architectural historian James Broadbent has described the drawing room at Burdekin House as ‘the definitive example of the architectural use of the style in the colony’. (James Broadbent ‘Louis XIV in Australia’, Australian Antique Collector, No. 38, July-Dec. 1989).

In this photograph Edwardian furnishings, including the frilled lamp shades, mix awkwardly with the cherubs of an earlier age.

Courtyard of Burdekin House, 1933

Burdekin House was owned and occupied by members of the Burdekin family from 1841 until 1922. When a hotel to be called the Waldorf Astoria was proposed for the site, the Royal Australian Historical Society unsuccessfully lobbied government to acquire the house for preservation. Instead in 1924 the house was bought by T.E. Rofe, a Sydney businessman and philanthropist. The back courtyard and the grand spaces on the ground floor were given over to the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Ladies' Auxiliary for fund-raising functions and the upstairs rooms were let as studios for artists.

Burdekin House Exhibition 1929

A major public exhibition of fine and decorative arts, known as the Burdekin House Exhibition, was held at Burdekin House from 8 October till 21 December 1929 in aid of the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. The exhibition consisted of a series of specially decorated rooms, with those on the ground and first floors decorated in various period styles while on the top floor, six small rooms were furnished in the ‘modern manner’. The modern rooms, decorated by artists such as Roy De Maistre, Thea Proctor, Hera Roberts, Adrian Feint and Leon Gellert, have come to represent ‘a pivotal moment in the history of Australian modernism’ according to art historian Martin Terry (in Sydney moderns: art for a new world, edited by Deborah Edwards and Denise Mimmocchi, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2013).

Burdekin House, Sydney, 1933

Burdekin house was offered for sale for a final time in 1933. It was purchased by the trustees of St Stephen's Presbyterian Church and demolished in August 1933 for a new church to replace the existing one in Phillip Street, itself demolished for the extension of Martin Place.

The demolition of Burdekin House created a groundswell of support for what today would be called heritage conservation and protection. In 1934, with the recent example of Burdekin House fresh in memory, the Royal Australian Institute of Architects led a campaign to save Bronte House in Sydney’s eastern suburbs from a similar fate by helping to raise funds that enabled its purchase by Waverly Council. Later in the decade when a government appointed Macquarie Street Replanning Committee was considering the removal of many historic buildings, architect Professor Leslie Wilkinson was one of many who publically raised his voice in opposition, stating that the demise of Burdekin House should not be repeated by the destruction of other buildings: ‘Macquarie-street used to be a beautiful street. Burdekin House was a stately feature of it, and the demolition of that historic building was a crime and a tragedy…’ (Sydney Morning Herald 12 February 1937 p.10)

Annie Wyatt, the driving force behind the establishment of the National Trust in NSW in 1945, was also deeply affected by the demolition of Burdekin House in 1933 and then the Commissariat Store at Circular Quay in 1939. Her son Ivor Wyatt later recalled that his mother referred to the destruction of these buildings as ‘official vandalism at its worst’ and ‘the final straw which stirred her to action’. (Ours in trust: a personal history of the National Trust, Willow Bend Press, Pennant Hills, 1987) In effect, the National Trust in NSW was formed as a direct result of the demolition of these two buildings.

Facade, Burdekin House, 1933

The demolition of Burdekin House was mourned by many Sydney-siders and many interested parties acquired architectural material from the house. The Sydney Mail reported in August 1933 during the demolition process that ‘in the reception room [drawing room] workmen were cutting out portions of the painted ceiling. These happily are to be preserved.’ Six painted panels were offered to the Vaucluse Park Trust for the sum of thirty guineas but the Trust declined the offer. The fate of the painted panels is a mystery but other elements are known to have been reused: the front door fanlight and sidelights were taken to Plumthorpe, near Barraba in north-western New South Wales by a Burdekin family decedent; the dripstone from the courtyard was acquired by the Royal Australian Historical Society; a Miss Kathleen Rutherford incorporated cedar doors, bricks and timber panels from Burdekin House into her new 1930s home at Palm Beach; and six of the ten columns were acquired, cut down and used to replace the existing cast iron flat grille verandah columns from the c1856 house, St Malo in the Sydney suburb of Hunters Hill.

Such was the status of Burdekin House that in 1939 the auction house James R Lawson, was still selling a range of goods advertised as coming from the house including English and Irish glass and goblets, six old mirrors, a Louis XVI carved mahogany three-fold screen 7ft 6in high, and two Georgian mahogany settees.

St Malo, Hunters Hill, 1956

St Malo, built around 1856, was just one of a number of cottages constructed at Hunters Hill NSW by brothers Jules and Didier Joubert between 1847 and 1880. It became Didier Joubert’s own home and was named after the home town in France of his wife, Lise Marie Bonnefin.

When Joubert’s daughter, Madame Rose du Boise, acquired the Burdekin House columns from the 1933 demolition she had the columns cut down to replace the existing cast iron flat grille verandah columns at St Malo. They were reduced from approximately four to three metres in height. Architectural historian Robin Boyd observed that the result produced ‘somewhat stumpy new proportions’. (The Australian ugliness, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1960)

In the late 1940s St Malo itself came under threat with plans to build an expressway through Hunters Hill and new bridges at Figtree and Gladesville. The National Trust of Australia (NSW) acquired a 20 year lease on St Malo in 1955 as part of a doomed campaign to save the property. The Trust sublet the house to Tinker Tailor Pty Ltd, an interior design company. The company renovated and furnished ‘St Malo’ in period style and then used the property for wedding receptions, dinners and luncheons.

Despite community protests, St Malo was demolished in June 1961, together with several other historic properties in Hunters Hill.

St Malo, 1957

The campaigns led by the National Trust of Australia (NSW) to save St Malo as well as Subiaco at Rydalmere on the Parramatta River were unsuccessful in the short term. Both houses were demolished in 1961 but the publicity generated by the campaigns resulted in a strengthening of public opinion in support of preservation of the built environment. The National Trust’s Historic Buildings Committee began identifying and listing buildings of heritage significance and in 1962, staged a landmark exhibition, No Time to spare, featuring 34 ‘A’ list buildings, ‘...the preservation of which is regarded as essential, whatever the cost.’

Community associations also emerged in Sydney concerned with preservation of their local historic areas: the Paddington Society, Glebe Society and the Hunters Hill Historical Society were all formed in the early to mid-1960s, the later in direct response to the demolition of St Malo.

Burdekin House column (detail)

Following the demolition of St Malo in 1961, a number of fittings and fixtures were saved and sometimes repurposed into other houses. The National Trust of Australia (NSW) retained the six verandah columns originally from Burdekin House. It donated two of the columns to the Scone Community Amateur Dramatic Society (SCADS) to be placed either side of the stage of their refurbished theatre in the Old Courthouse at Scone NSW. The four remaining columns were kept in storage eventually emerging at the National Trust’s head office at Observatory Hill. In 2012 the remaining four columns, only one with a surviving capital and base, were acquired by the Caroline Simpson Library.

Cleaning and minor repairs of the columns has revealed that they are not all identical. Two are made of an Australian hardwood and the others of oregon, a timber imported into Australia as early as the 1850s. The Oregon columns have deeper and wider fluting than the Australian hardwood columns. The reason for the difference in timbers and manufacture is currently being investigated but may point to replacement sometime during the turbulent lifetime of these true survivors.

Published on

Related

Burdekin House columns

Burdekin House was once described as one of the finest buildings in New South Wales and one of the sights to see when visiting Sydney

Salvaging a future for Sydney’s demolished buildings

When important historic buildings were demolished in 20th-century Sydney, one way to remember them was by saving, perhaps for re-use, some of their more notable architectural features

Past exhibition

Home in the Hunter

A look at the changing fortunes of pastoral estates of the Hunter Region

Documenting NSW Homes

Recorded for the future: documenting NSW homes

The Caroline Simpson Library has photographically recorded homes since 1989