A long shadow: convict Sydney and the Hyde Park Barracks

Hailed for its architecture, and now World Heritage listed, the Hyde Park Barracks has much more to tell us about the changing experience of convicts and the growth of a restless colony.

A costly experiment

For prisoners cowering in a London courtroom, the solemn decree ‘transportation beyond the seas’ must have sounded surreal. Mercifully spared the gallows, they’d soon be sailing 13,000 miles from home, to Australian shores. Between 1788 and 1868, some 166,000 British men, women and children took that fateful voyage, a miserable cargo of felons and misfits dispatched to the Australian colonies, caught in the grinding gears of convictism. Few would ever return.

The 2010 listing of 11 Australian Convict Sites – including the Hyde Park Barracks – on UNESCO’s World Heritage register sheds light on the enormity and complexity of what was, in effect, an 80-year experiment in crime control and colonial expansion. Indeed, no other nation-state, before or since, has sprung from the seeds of a convict colony. The listing also underlines the terrible cost of nation building: to the Aboriginal societies whose country and resources were plundered as the colony expanded, and in the ongoing legacy of Aboriginal pain, anger and dislocation. Here, in this fraught interplay of creation and destruction, lie the foundations of convict Australia.

Convict facts

Distance of voyage from London to Sydney

13,000 miles (21,000 kilometres)

Number of convict ship voyages

840+

Convicts through the Barracks 1819–48

about 50,000

Most common crime

stealing (17%)

Number of convicts named John Smith

603

Youngest Hyde Park Barracks convict

9-year-old thief John Dwyer

Noisy old town

Rewind to 1807. Imagine you’re a bird soaring over Sydney, tracing the course of a stream emptying into the cove: descending through the valley, crisscrossing cart tracks, cottages, granaries, passing the powder magazine, lumberyard, jail and hospital, dodging the creaky sails of the government windmill before coming to rest on a flagstaff crowning the Dawes Point ridge line, high above the harbour. Below is a noisy town, a maze of high streets and lanes, row-houses, pubs, butcheries, bakeries, breweries, tailors, tanners and turners, hemmed in by the shoreline, where wharves, docks, slipways, sail rooms, sawpits and boathouses line the silted banks.

Incredible as it seems, despite its many guards and soldiers, this was the convicts’ town, and these homes, businesses, attractions and distractions were the everyday realities of convict life at this time. Contrary to today’s common perception of flogged and degraded brutes worked to death in chains, here was a vibrant community of citizen-convicts, living in family units, wearing the latest fashions, operating businesses and trading their savings, skills and capabilities for comforts largely unheard of back in England. What’s more, convicts were allocated ‘free time’ to undertake private work and chores to support themselves and their families once they’d completed a minimum level of work ‘under sentence’, set by colonial officials.

A barracks rises

Fast forward to April 1817. Stringlines are being strung across a bushy patch of ground at the far end of Macquarie Street. Soon after, convict men drive shovels and mattocks into dry and root-ridden earth, their backs twisting and straining as scrub and grass are torn loose.

Now picture a construction site: a clatter of stonecutters and setters, mortar men, brickies, plasterers, mechanics and painters, of creaking carts and hoists, the sway of miraculous scaffolding, the clang of blacksmiths’ hammers, the rasp of sharpening tools, the swagger of labourers, curses and song. Policing this motley rabble are the overseers and constables, sentries and mounted soldiers, eyes out for loafers and troublemakers.

Looming steadily is the Hyde Park Barracks, a big brick building with rows of large windows. Inside are 12 spacious wards, soon to sleep 600 male convicts. When the barracks opened in June 1819, it sat in the centre of a broad dusty courtyard, ringed by perimeter buildings – offices and utility rooms, cells, a bakery, kitchen and mess halls. Along the back wall were toilets and a well. At the front were timber entrance gates, painted blue, hinged on hefty stone pillars with guardhouses to monitor the movement of men and materials in and out of the compound.

To some, here was an architecture of grace and style, of pleasing rhythm and proportion, surprisingly sprung from the mind of a convict, Francis Greenway – an architect canny in classical forms and fashions. Even Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s political foes were reluctantly impressed, conceding it handsome, well executed and sure to be durable.

To the convicts, the barracks was far less appealing. With its gates and walls, here was a building to make life more difficult, a place of restraint, ridden with rules and regulations. To many, it looked like a workhouse. It even had a clock to govern their time.

New order

Built initially to solve a pair of short-term problems (rising crime and homelessness in Sydney), the barracks upset the old order for all convicts. The formerly ‘unshackled’ and enterprising convict community balancing its own needs and aspirations with the practical needs of government came to an end. The new order placed government priorities at the forefront – public infrastructure, courts and churches. The barracks also helped to spearhead a new way of organising convict labour. Here would live an ‘able-bodied’ workforce, marched out each morning in closely controlled gangs to construction sites, quarries, docks, workshops and gardens, and after a full day’s work, returned each night to eat, before sleeping alongside each other in spartan dormitory wards.

Up country

Around 1822, as Sydney’s skyline grew, the colony changed tack again, shifting its focus from public works to pastoral expansion. And as a result, the legions of skilled and productive convict artisans, mechanics, apprentices and labourers found themselves reassigned to private ‘masters’, as shepherds, shearers, harvesters, land clearers and loggers. This shift also altered the role of the Hyde Park Barracks, which now served mostly as short-term lodging for newly arrived convicts or those being shunted between distant farming estates under the assignment system.

In the 1830s, an influx of immigrants, commercial growth, and the first whiffs of self-government and an independent press were kindling hopes of a convict-free colony. But Britain saw things differently. It still needed somewhere to send its criminals. So while nouveau-riche merchants built showy new villas around the Sydney foreshores and along its airy ridges, more and more convicts found themselves toiling in distant ‘iron gangs’ carving out country roads, facing ever more severe punishments, or rotting away in miserable penal settlements far from Sydney.

Throughout the decade, a miasma-like fear of convicts crept through the colony. Newspapers printed chilling stories of desperate runaways robbing and assaulting travellers, or evoked the spectre of convict rebellion. At the same time, outlying convict communities along the colony’s expanding frontier had long waged campaigns of terror against Aboriginal groups.

Finally, a damning parliamentary inquiry into the evils of transportation stopped the convict ships to Sydney in 1840. As the remaining convicts served out their sentences and the convict infrastructure was wound down, the barracks overflowed with hardened and intractable ‘old lags’ returned from assignment.1

End days

It’s 1840. Standing in a dusty courtyard bathed in afternoon sun is newly arrived convict Charles Cozens, a tall ex-soldier, facing a 14-year sentence. The Hyde Park Barracks compound, he discovers, is sordid and grim. After three decades of use, the main building is ‘large and gloomy’. Tonight, 1300 souls will sleep here. Suddenly the entrance gates are flung open and the courtyard fills with convicts, marched back from their labours around town. The men enter in silence. Once inside, they’re noisy and fearsome, as if ‘inmates of some gigantic Bedlam had actually broken loose’. Here was a chilling spectacle: ‘a dense mass of moving forms, of every variety of face and figure … every evil in human shape, a perfect accumulation of vice and infamy …’2

By the mid-1840s, Sydney was a booming metropolis, its streets lit by gas lamps, its docks humming with global trade and its shops brimming with the latest in European fashions and fancy goods. Out on the edges of town, merchants, bankers, shopkeepers and office workers had built terraced homes and garden cottages in new suburbs. Forlorn in its courtyard, the barracks had gone from eye-catching, ‘an idea of towering grandeur’,3 to an object of ridicule and shame. For Cozens, now a free citizen, the ‘extinction [of] that most disgraceful monument ... will be an act of justice and judgment on the part of the citizens of Sidney [sic]’.4

Sure enough, in January 1848, bending to public outrage and the interests of local businesses who saw subsidised labour as a brake on economic growth, the Convict Department was closed down and the barracks decommissioned. From its wards were marched just over a dozen ‘old hands’, the final dregs of convict Sydney en route to Cockatoo Island, the Alcatraz of Sydney Harbour.

A long shadow

Today, the Hyde Park Barracks is a rare survivor, hunched on the city’s eastern ridge, flanked by leafy parks and wide streets, facing the town as if peering across time. As a lucid witness, it speaks of a shape-shifting settlement, its future uncertain, wrestling with its convict DNA. For those who lodged here, life went from hopeful to harsh. In the end, the system they endured was condemned as shameful and defective. But in spite of efforts to expunge the so-called ‘stain’, the brutal history of convictism – as an agent of both colonial growth and Aboriginal devastation – lingers in the national consciousness.

Notes

1. Transportation continued to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) until 1853. The last convicts arrived in Western Australia in 1868, marking the end of all transportation to Australia.

2. Charles Cozens, Adventures of a guardsman, Richard Bentley, London, 1848, p116.

3. Sydney Gazette, 17 July 1819.

4. Wendy Thorp, Hyde Park Barracks Museum Conservation Plan, vol 1: October 2016, p45, quoting Cozens, Adventures of a guardsman.

Related

Convict Sydney

Convict Sydney

From a struggling convict encampment to a thriving Pacific seaport, a city takes shape.

Published on

Convict Sydney

Convict Sydney

James Hardy Vaux

Some convicts were transported more than once. Vaux was sent to the colony three times, each time arriving under a different name.

Convict Sydney

Sandstock Bricks

Sandstock bricks such as these were the building blocks of Governor Macquarie’s ambitious public works scheme for Sydney

Convict Sydney

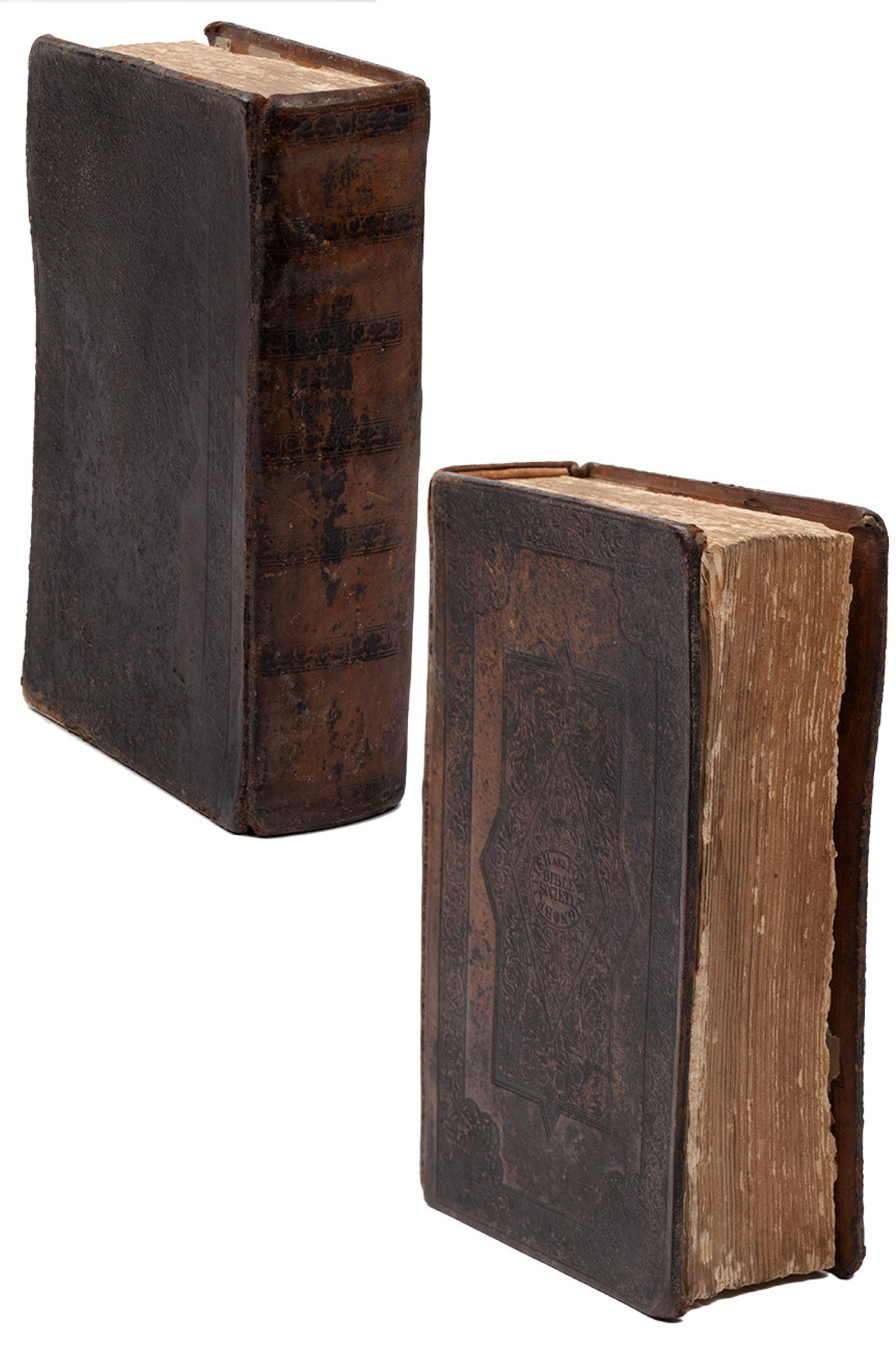

Bible & Prayer Book

The name and the date 1837 written inside the covers tell us they once belonged to an English brass founder named Thomas Bagnall

Convict Sydney

Hammock Scrap

A few scraps of rope and coarse, but finely woven flax linen scraps like this one are all that’s left of the hundreds of hammocks that originally lined the convict sleeping wards