The Collection: NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive

Nestled between Sydney Harbour and the city skyscrapers is a squat cluster of sandstone buildings known today as the Justice & Police Museum. Occupying what was once one of the colony’s busiest legal complexes, the museum cares for an eclectic collection of material relating to Sydney’s criminal and policing history.

This includes the remarkable New South Wales Police Forensic Photography Archive, made up of approximately 130,000 negatives in both glass-plate and cellulose film formats. Taken between 1910 and 1964, the images in the archive document, in all their gritty and at times confronting detail, Australia’s ‘Sin City’ – its people, their misfortunes and their crimes.

Like many genesis stories, the archive’s starts with a flood. Sydney is prey to spectacular storms that deluge the city with fast-flowing water, which spills over gutters and silently makes its way into roof cavities and basements. In 1990, after one of these storms, New South Wales police checked on a storage space used to house photographic negatives from historical investigations. Water had seeped into the wooden chests holding the negatives and an ominous sludge had formed in the base of each. Police contacted staff at the Justice & Police Museum, and a salvage operation began. The collection was washed, dried and repackaged. On investigation, it proved to contain intriguing and at times startling images of a Sydney long gone. However, the indexes and paperwork that explained why the photographs were taken had been lost over the years, leaving museum staff with an interpretive challenge. The negatives were placed in a museum storeroom and left in peace again for almost ten years, waiting for a new meaning to be created for them.

During the 1990s, a fashion emerged for reinterpreting historical photographic collections not originally intended for public consumption, such as those in police archives. Pioneering work by writer Lucy Sante in 1992 on the New York Police Department collection ignited the imaginations of many researchers and artists. Academics and curators in Sydney were also inspired. In 1999, the Justice & Police Museum presented Crime Scene: Scientific Investigation Bureau Archives 1945–1960, an exhibition curated by academic Ross Gibson and artist Kate Richards showcasing images from the forensic photography archive. This was followed in 2005 by an exhibition that became the most popular ever held at the museum – City of Shadows: Inner-city Crime and Mayhem 1912–1948, curated by crime-writing academic Peter Doyle. The public embraced the sometimes macabre content, which included crime scene images, and clamoured for more stories from the archive. Museums of History NSW (previously Sydney Living Museums) has since created publications, programs and further exhibitions featuring the photographs.

The ‘Specials’

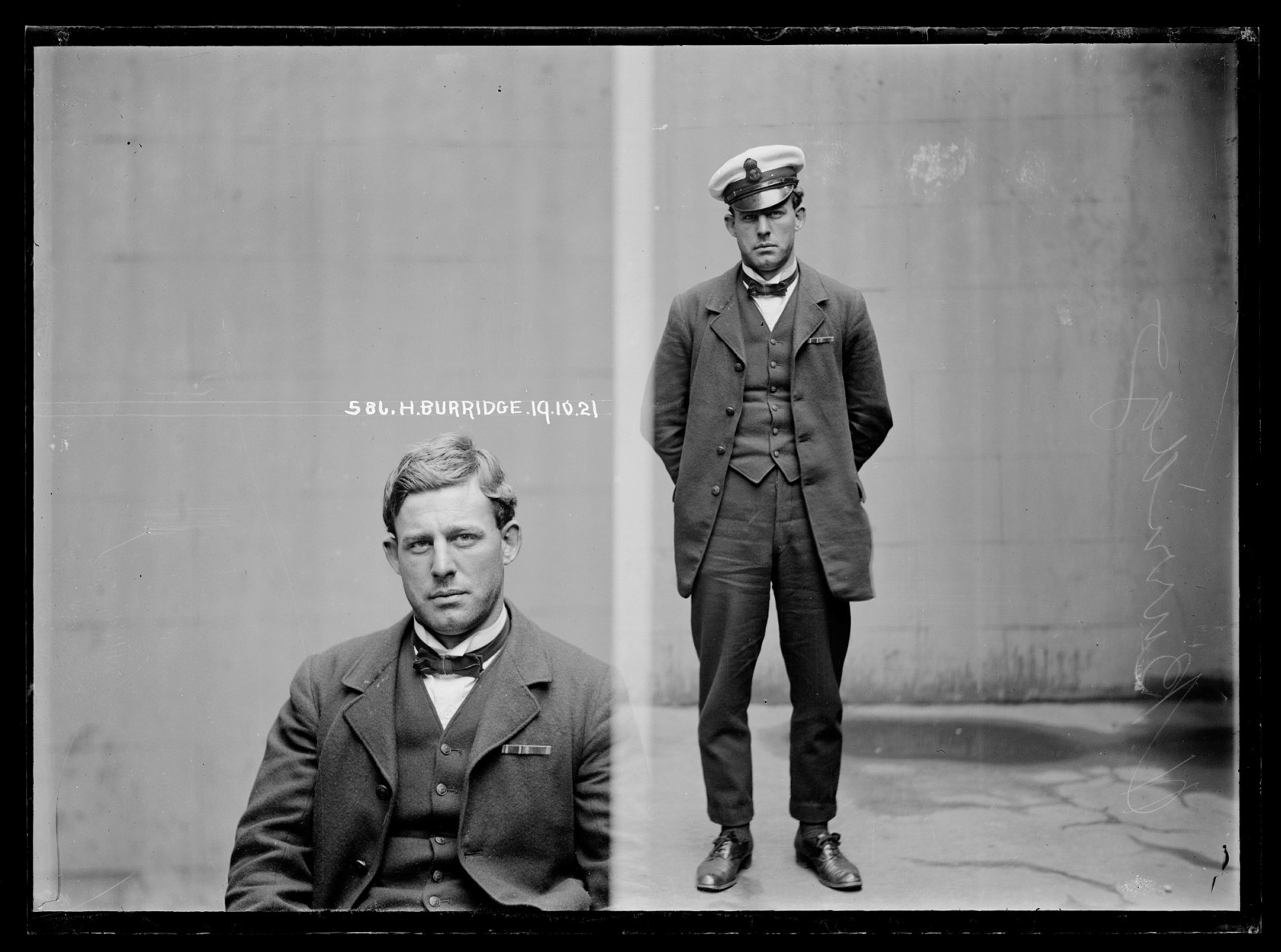

The most popular images in the archive are those known as the ‘Specials’, mugshots of suspects in police custody, and especially those photographs taken between 1920 and 1930. We do not know why the police named the photographs ‘Specials’, but the term hints at the rare and inviting qualities of these images, and at their contravention of the norms of police mugshots. Unique among international police photography, the Specials capture both the physical characteristics of the suspect and a glimpse of their personality. Our research indicated that the Specials’ remarkable aesthetic may be the creation of police photographer George Howard, whose ‘artistic proclivities’ were noted in contemporary newspaper reports.

Most of the Specials were taken outside the holding cells at Central Police Station, one of the busiest stations in Sydney. The people in the mugshots are suspected of a crime and some have been charged with an offence, but they are yet to have their day in court. Generally the photographs show a close-up of the suspect’s face and then a wider shot of the person, often standing near a bentwood chair, included to give a sense of the person’s height. The photographer was responsible for ensuring that vital information about the suspect was recorded with the image. This evolved into a system where the date, the suspect’s name and fingerprint classification, and, on occasion, a reference to a previous police file were inscribed onto the emulsion (reverse) side of the glass-plate negative. Police mastered the technique of writing back to front so that the information was legible in the photographic print.

By the 1920s, the mugshot – even strikingly unconventional ones such as the Sydney Specials – had become a key policing tool in the western world. The Specials were probably used primarily to familiarise police with the city’s criminal milieu and to tip them off about troublemakers. The images were sometimes collated in books, and written beneath each image was the category of crime with which the individual was charged. Police may have used the books for quick identification of likely suspects when investigating a crime. However, the Specials’ informality and the lack of telltale signs that the person was in custody, such as handcuffs, meant they could also be shown to a witness during the investigation of a crime without prejudicing them against the suspect. The police photographer did not interfere with the suspect’s choice of pose, perhaps in order to capture a more candid – and, for policing purposes, more useful – shot.

Another unusual feature of the archive as a whole is the fact that it is made up of negatives and not photographic prints, giving us access to the complete, undoctored images. The police photographers never expected that the entire image would be viewed by the general public, so they often left their leather equipment bags in shot and did not worry about bystanders being in frame. ‘Photobombing’ police or other crims appearing in the background were literally whited out of the printed image, which was reduced to a tight shot. Today, digital technology allows us to view details in the negatives that were removed from, or indistinct in, surviving photographic prints. The texture of a coat, the teardrop in a suspect’s eye or the medal pinned to the returned serviceman’s chest can all be examined using photo editing software. The effects of water, clumsy handling and natural ageing mark the glass-plate negatives, and all the losses, chips, silvering and fingerprints have now become part of the archive’s story.

Related

WW1

A dubious defence

On 19 October 1921 Herbert Burridge was listed in the New South Wales Police Gazette as a deserter from HMAS Cerberus

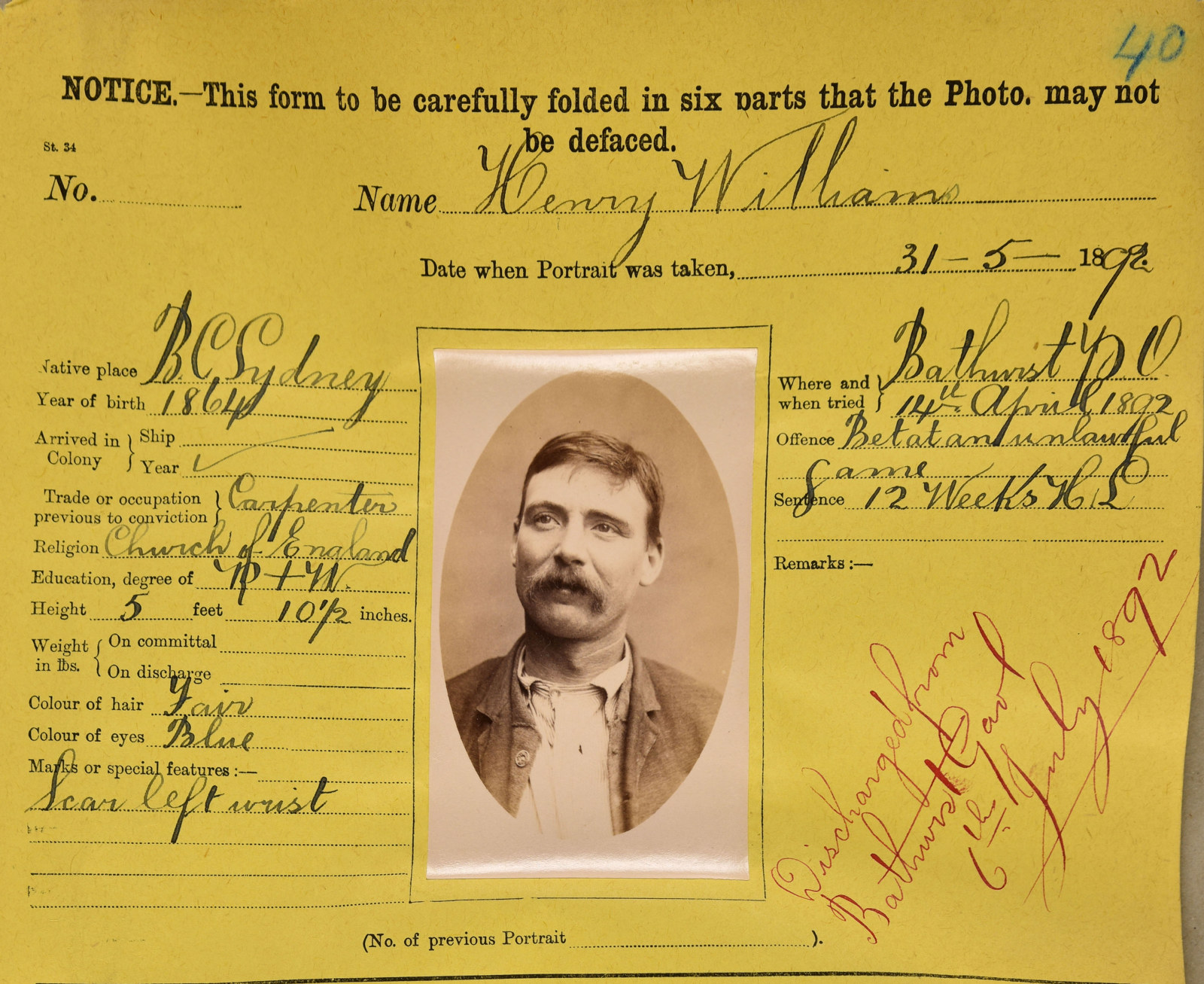

Archives behind the scenes - gaol photos

In this episode we show you the very popular Gaol Photo Description Books. The photos (or mugshots) of prisoners are from gaols right across NSW and date from 1870-1930

Published on