Painting the Rocks: the loss of Old Sydney

The chance find of a 1902 catalogue in the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, inspired the 2010 exhibition at the Museum of Sydney, Painting The Rocks: the loss of Old Sydney.

In 1902 An exhibition of pictures of Old Sydney featured scenes of The Rocks and Millers Point painted before parts of them were demolished in the name of public health and morality, and changed forever. Our exhibition restaged and reinterpreted this little-known exhibition.

Following the outbreak of bubonic plague in Sydney in 1900, waterfront areas along Darling Harbour, Millers Point and The Rocks were resumed by the government. The outbreak of plague appeared to confirm views widely held by both the authorities and sections of the public that the district was one of Sydney's most notorious slums, with decrepit housing, inadequate sanitation and poorly clad street children. The city improvers commissioned photographs to document the substandard housing and lack of sanitation; no part of Sydney had ever been depicted so intensively.[1] The plague provided 'an opportunity seized by the government, with the sanction of public opinion, to both control and reshape the city's wharves, and to purge the city of its perceived moral, physical and social ills'.[2] Over the next 15 years many hundreds of homes would be torn down, whole streets would disappear and the waterfront would be reshaped. The area would become 'one of the most intensely governed and directed areas of the city'.[3]

The rapid disappearance of the few remaining bits of old Sydney—the Sydney of 60 years ago— serves to remind us of what the city used to be, and recalls the figures of well-known citizens who have long since joined the great majority in the land of shadows.

Joseph Michael Forde, Some fragments of Old Sydney gathered by Old Chum, McCarron, Stewart & Co, Sydney, 1898

Julian Ashton, a leading artist of the day, and was concerned that the loss of these oldest areas of Sydney would pass unnoticed. He employed his persuasive powers to induce the Minister for Works, E W O'Sullivan, in charge of the reconstruction of The Rocks and Millers Point, to grant £250 for the acquisition of drawings and paintings of parts of 'Old Sydney' that were about to be lost to redevelopment. Artists were invited to paint 'some of the quaint and picturesque cottages and structures at "the Rocks" before they are demolished'.[4] 'In this way they would record remnants of Sydney's colonial heritage before its transition to a 20th-century metropolis.

Nothing remains of Clyde Street today. It disappeared about 1909 when the area was quarried to create Hickson Road.

These paintings of The Rocks and Millers Point stand in sharp contrast to those views critical of the area and its inhabitants.

The old exhibition catalogue found in the Mitchell Library is a complete list of the 145 works exhibited at the Society of Artists' rooms on Pitt Street in March 1902. The Painting the Rocks exhibition at the Museum of Sydney brought together over 30 of these works by artists such as Howard Ashton, Julian Ashton, Clarence Backhouse, Fred Leist, Sydney Long, Alice Muskett and H Stuart Wilson.

These paintings of The Rocks and Millers Point stand in sharp contrast to those views critical of the area and its inhabitants. They do not depict these areas as squalid slums. The people in the paintings are not derelict and hopeless, given to gin, whisky and gambling.

We see scraps of domestic life spilling out beyond the interior sphere. Indeed, many of the images portray vignettes of domestic life lived outdoors, as was necessary given the cramped living conditions of the average family home. Houses, pubs and shops of mixed colonial pedigree, street hawkers, children playing in the street, makeshift clothes lines, cottages with wide eaves, horse-drawn carts, gas lamps, sailors, goats and chickens are all lovingly depicted.

By rendering one of Sydney's most notorious slum districts in picturesque and sentimental terms, with local residents at the heart of the pictures, the artists proposed an alternative set of urban, social and aesthetic values. They also provided a unique and detailed view of everyday life in Sydney's oldest neighbourhood at the turn of last century.

Painting the Rocks placed the 'Old Sydney' paintings alongside the images that form the official history of the time, the record that allowed those driven by political and commercial interests to promote, in the name of the public good, the resumption and demolition of property in the area.

Authorities' concerns about The Rocks and Millers Point were a microcosm of the urban issues that faced Sydney at the turn of the century. The 1902 'Old Sydney' exhibition can be read as the beginnings of urban preservationist activity through which artists and antiquarians sought to document and preserve colonial architecture in the face of the perceived homogenisation of the city. The value of these works is heightened today by Sydney's ongoing love of continual development and change.

What are we doing at the present day in the way of preservation of historic spots and landmarks in our city and country? This is a question which every year becomes more and more insistent.

Frank Walker’s 1907 call to arms in ‘The historic landmarks of Sydney: their need of preservation’, Art and Architecture, May-June 1907, p.88

Notes

1. New South Wales Government Architect, 'Plans and photographs of buildings demolished, 1902- 1907', Mitchell Library, SLNSW.

2. G Karskens, Inside The Rocks: the archaeology of a neighbourhood. Hale & lremonger, Sydney, 1999, p65

3. S Fitzgerald &C Keating, Millers Point: the urban village, Hale& Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, p65

4. The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July 1901, p6

Published on

Collections

‘The people’s house’: what’s in a name?

The ‘Sydney Opera House’, the ‘Opera House’, or simply ‘the House’ – we know it by many names. But why is this Australian icon also called ‘the people’s house’? Exhibition curator Dr Scott Hill explores the story behind a name

First Nations

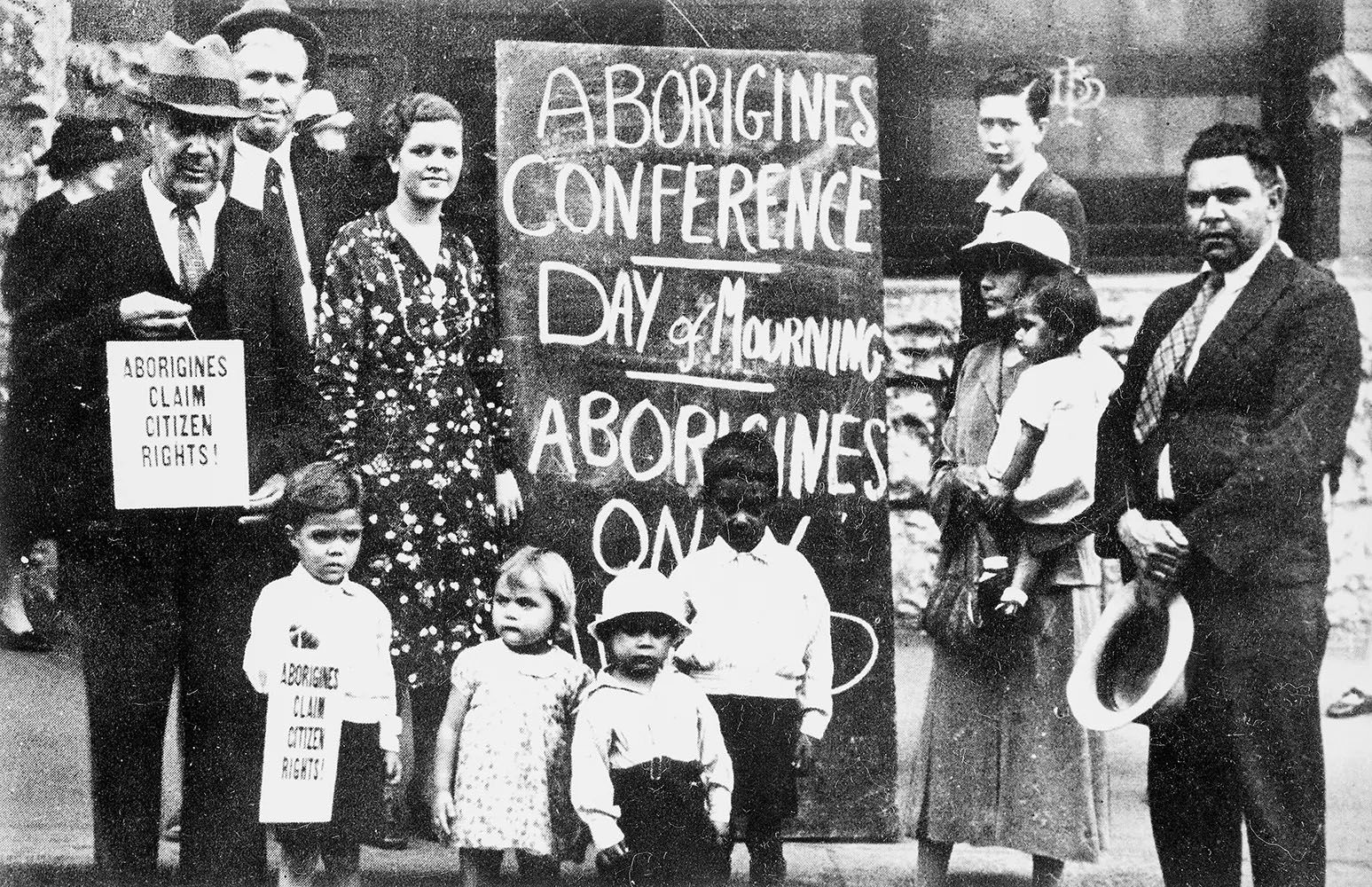

Day of Mourning

January 26 has long been a day of debate and civic action. Those who celebrate may be surprised of the date’s significance in NSW as a protest to the celebrations of the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet on what was then “Anniversary Day” in NSW

Collection insights from a guest refugee curator

Jagath Dheerasekara has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions and his work is held in both institutional and private collections across Australia