Preserving our culinary heritage

Autumn is the time when families like the Rouses of Rouse Hill Estate preserved the last of the warmer weather’s bounty to enjoy in the months to come.

It’s hard to imagine a time when you couldn’t buy a fresh tomato, cucumber or lemon for several months of the year. Artificial refrigeration, and particularly refrigerated transport – domestic and global – has enabled us to eat such foods year-round. With this convenience, however, we’ve become removed from the seasonal rhythms that once shaped the way we cooked and ate. The cultural value and emotional connections that we place on our food have also been affected, diminishing our wonder and joy as the seasons progress and rotate. Mangoes and cherries in the summer months may still be special for many of us, but lamb and asparagus, or duck with peas, once ‘signature’ dishes of springtime, can now be made all year.

Transported tastes

Making the most of produce in season has been integral to culinary development and many cultural traditions. In places that experience lean periods, often due to climatic conditions and cycles of extremely cold winters or intensely hot, dry summers, preserving foods was essential for survival. Settlers migrating to Australia from the northern hemisphere transported longstanding preserving practices along with their crops, livestock and agricultural systems. Despite Australia’s relatively temperate conditions, these practices were continued to ensure a supply of preserved foods that had become traditional dietary staples, many of which we still enjoy today.

A seasonal cornucopia

Through cookbooks and recipes found at Rouse Hill House & Farm, along with letters and memoirs, we learn that the family made the most of foods in season. Like most large landholders in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Rouses produced much of their own food on their estate, northwest of Sydney. They kept chickens for eggs and cows for fresh milk, cream and butter; maintained a kitchen garden and asparagus beds for vegetables and herbs; and enjoyed fruit such as citrus, figs and peaches from an extensive orchard planted on the sloping ground on the southern side of the house. ‘Jam melon’ – a bland, almost flavourless fruit that looks from the outside like a watermelon – was used to make jam, adding bulk to rarer fruit such as pineapple, or imported ginger.

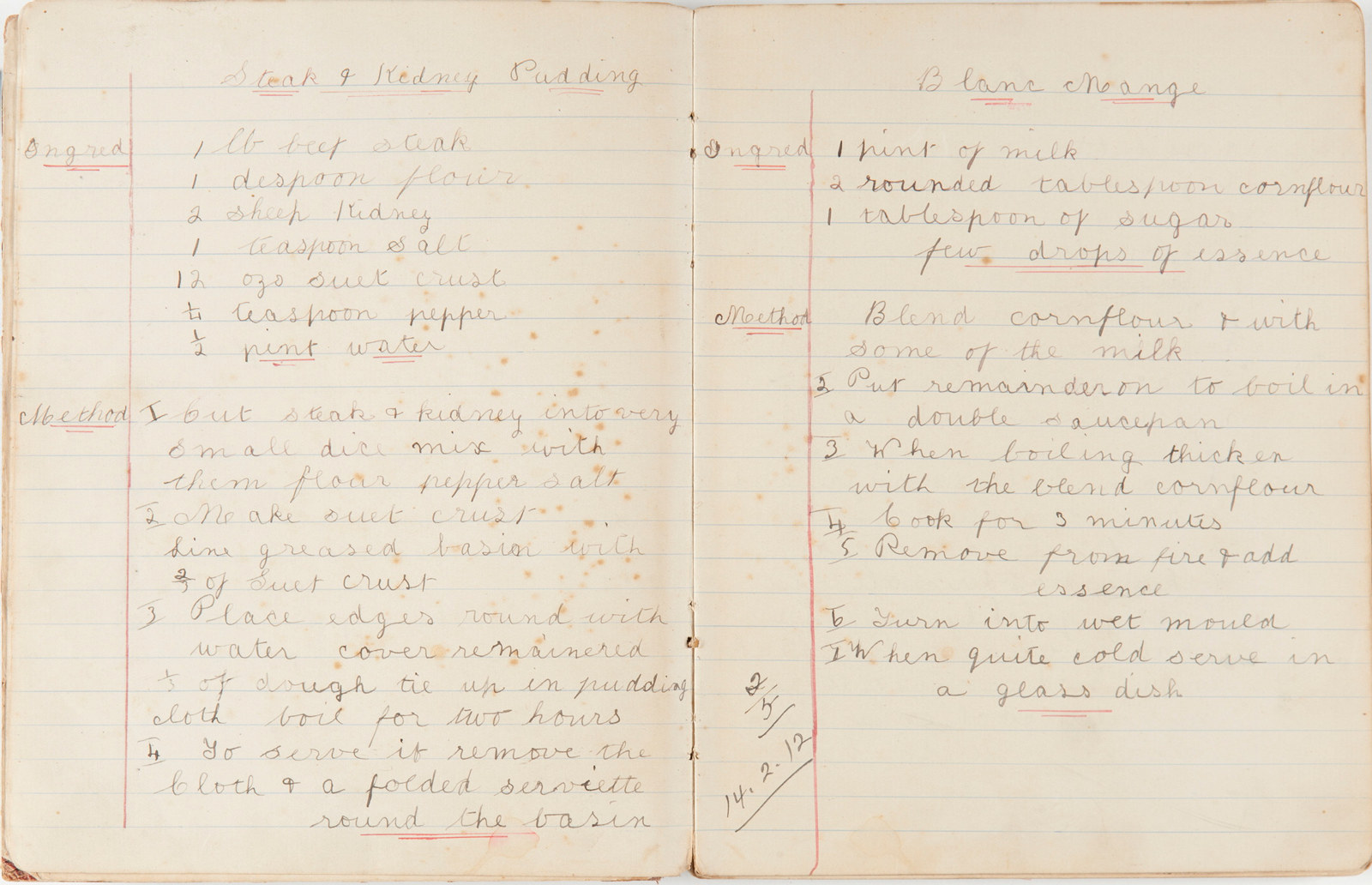

Telltale marks and splatters in the family’s surviving cookery books and manuscript recipes reveal the dishes that were made by generations of Rouse family cooks for over 100 years. Orange splodges in an 1863 cookbook suggest that carrot pudding was made at least once; like many root vegetables, carrots could be stored for several months in tubs of sand in a cellar or similarly dark, cool place.

Apples also store well, and apple recipes in the Rouse cookbooks show signs of repeated use. Family histories describe Nina Terry (nee Rouse) treating the family to apple snow (an uncooked meringue of poached apples folded through whipped egg white). Apple charlotte was a good way to transform apples and stale bread (which forms the charlotte’s crust) into another delicious dessert.

A pantry full of preserves

The Rouse collection shows evidence of many delicious and practical ways to use and preserve excess fruit and vegetables. Tomatoes and other fruit were bottled for year-round use, a process made ‘safe and easy’ by home-preserving kits. Among the various boxes of items in the cellars beneath Rouse Hill House are the remnants of a Fowlers ‘Vacola’ ‘bottling outfit’ from the early 1950s. Fruit was tightly packed into specially manufactured glass jars, sealed with lids held tight with clamps, and boiled in a large metal canister. The tomatoes page in the instruction booklet is heavily marked with dark red splatters. A bottle of preserved peaches that remains in the storeroom adjacent to the kitchen and scullery also suggests the kit was put to good use.

Tomatoes could also be made into sauce or ‘catsup’ (ketchup), cooked down with vinegar, salt and spices; sugar, garlic, onions and apples appear in some versions. A handwritten tomato chutney recipe found tucked into a children’s book that belonged to Kathleen Rouse (recipe below) offers a delicious and practical way to take advantage of late-season tomatoes and the first of autumn’s bounty of apples, as well as pantry staples such as dried dates and raisins. A ‘mustard pickles’ recipe similarly shows how a miscellany of vegetables could be preserved piccalilli-style.

Even eggs were preserved. Hens produce fewer eggs in the colder months, and household management guides provide advice for storing them for extended periods. A jar of Ke-Peg, a commercial gel-like product to coat the egg and prevent air permeating the porous shell, survives at Rouse Hill House.

Precious traditions

Today, with refrigeration to keep food fresh there’s little need to maintain these age-old preservation practices. But there’s definitely a desire to continue many such traditions. Not only do they prevent waste in times of abundance, they’ve also created a vast array of food products that are embedded in our food culture. Beyond the obvious jams, chutneys and pickles, making cordials and alcoholic beverages such as wine was also a traditional way to use fresh produce in season. Cured meats such as corned beef, bacon and ham were often combined with dried legumes for minestrone or pea and ham soup as ‘comfort food’ in the cooler months. Similarly, dried fruit and the foods made with them – especially fruit cake and plum pudding at Christmas – are prime examples of resourcefulness when there was little fresh fruit available in the northern hemisphere winter. Even butter and cheese are the product of preservation. We don’t think of these foods as a means to extend the base products’ ‘shelf life’, but have developed a taste for them in their own right, and made places for them in our cuisine. They remain an important part of our food heritage.

Preservation techniques

Various preservation methods have been developed to prevent the growth of bacteria that makes food spoil. Bacteria need air, moisture and relatively neutral pH levels to survive, and they flourish best at 36.5 degrees Celsius (blood temperature). Perishable foods need to be altered to impede or eliminate harmful bacteria, or kept in an environment that prevents or inhibits the growth of these bacteria. Often, a combination of the following processes or interventions is used.

Denying bacteria oxygen inhibits their growth; this can be achieved by storing foods in airtight vessels or in bacteria-resistant mediums such as honey, concentrated sugar syrup, alcohol, oil or fat.

Air or sun drying is the oldest method of food preservation. Foods can also be dried in an oven or kiln, or hung near a fire or in a chimney. Salt is used to draw out moisture, and in high concentration inhibits bacterial activity.

Salt (sometimes with sugar) is used to dry-cure meat and fish (like prosciutto and gravlax) and to brine products such as corned beef – the ‘corn’ refers to the coarse granules of salt used.

Sugar is used to preserve fruit, as in candied oranges or ginger in syrup, and jam. The boiling of jam removes excess moisture, which increases the sugar concentration.

Fermenting involves creating an environment in which ‘good’ bacteria are produced to consume ‘bad’ bacteria – for example, salting cabbage for sauerkraut or kimchi; soaking olives, which are then brined; and introducing live cultures to milk for cheese or yoghurt, or yeasts or a sourdough ‘mother’ to bread dough.

Due to its acidity, vinegar is a useful medium to preserve vegetables and fish, producing foods such as chutneys, pickled herrings or ‘roll-mops’.

Reducing the temperature of foods to 5 degrees Celsius or below also inhibits bacterial growth and extends a food’s keeping time; freezing extends this even further. Heating foods (cooking) to 60 degrees Celsius kills most bacteria, or 75–80 degrees in the case of salmonella or listeria in chickens or eggs.

Recipe: Tomato Chutney

This recipe has been adapted from the original, which was handwritten on a piece of paper found inside Good things made, said and done for every home & household (c1885), a children’s book that belonged to Kathleen Rouse. The chutney is delicious with meat and cheese, and is a must for a ploughman’s lunch or on a good beef or kangaroo burger.

Ingredients

2kg tomatoes, roughly chopped

1.25kg green apples, peeled and chopped

500g seedless dates, chopped

500g raisins (or sultanas), chopped

90g onions, chopped

90g large red chillies, seeds removed, chopped

90g fresh ginger, chopped

70g garlic, chopped 90g salt

500g (2 1/2 cups) brown sugar

2l (8 cups) malt vinegar

Method

Put the tomatoes, apples, dates, raisins, onions, chillies, ginger and garlic in a food processor and process for 10–20 seconds to produce a roughly textured consistency. Transfer the mixture to a large saucepan and add the salt, sugar and vinegar. Bring to simmering point and cook for about 1 1/2 hours, stirring as the mixture thickens to prevent it sticking to the pan. When the chutney has reduced to the desired consistency (this depends on the type of tomatoes used and your preference), bottle and seal it in sterilised jars.

Makes up to 3 litres

This and other recipes and food stories from our collections can be found in the Eat your history book (available online at slm.is/shop) and on the Cook and the Curator blog: slm.is/cooking

Published on

Recipes

Browse all

A manuscript cookbook from Meroogal

Cooking was an integral part of the rhythm of life for the family at Meroogal, near Nowra on the south coast of New South Wales

Bischofsbrot (Bishop’s Bread)

Studded with colourful glacé fruits, Bischofsbrot, or Bishop’s bread, is an egg-rich, sweetened loaf popular in northern Europe

Don’t forget your homework

In a simple ruled exercise book, with margins drawn neatly in red ink, are over 60 pages of handwritten recipes, cooking rules and techniques, recorded by 12 year old Jenny (Dolly) Youngein, 104 years ago

Cook & Curator

Eier auf Florentiner Art (Eggs Florentine)

This classic recipe is simple to make yet rich and flavoursome. Perfect for a weekend brunch or a light supper