Vali Myers: teenage Ikon in street photograph

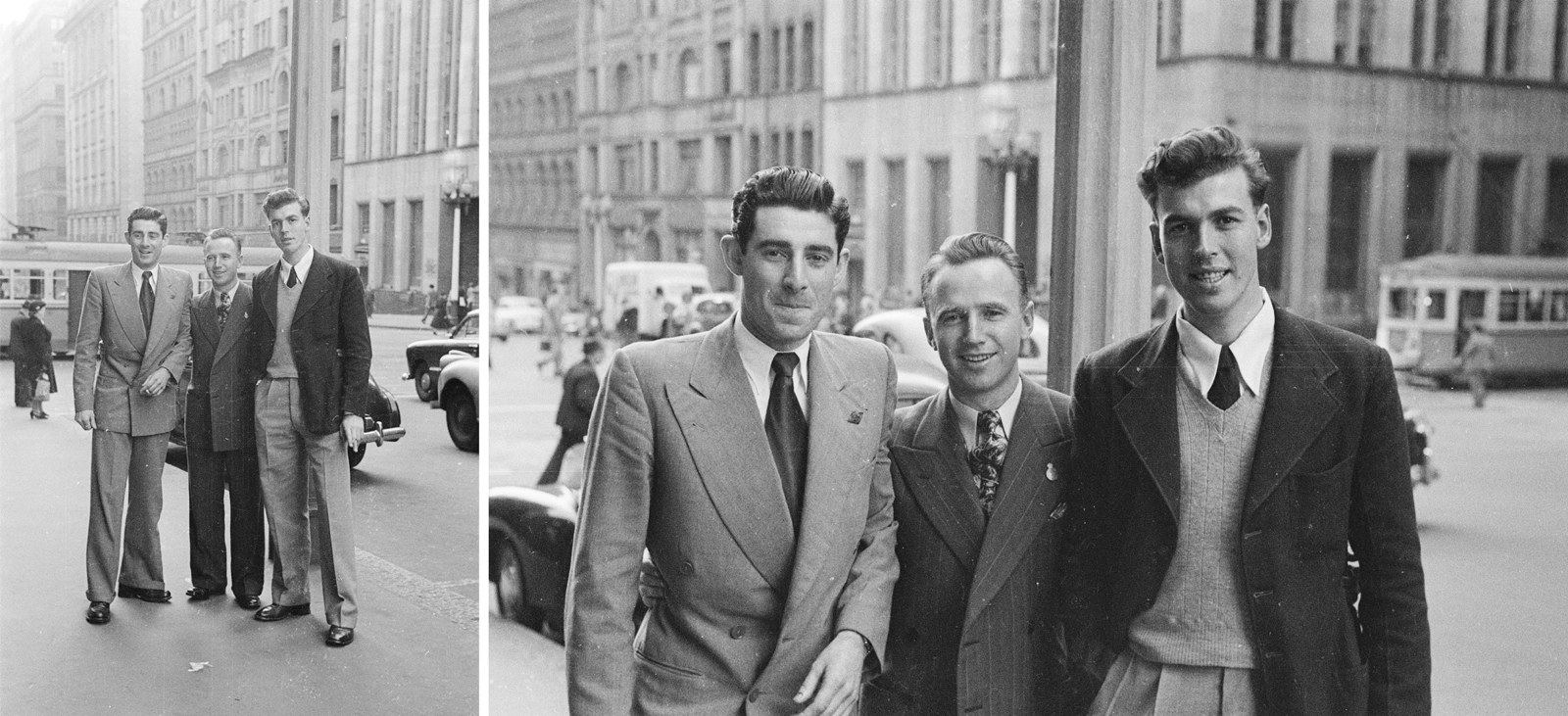

Two young women stride confidently, hand in hand, up Sydney’s Martin Place on a sunny winter’s day in 1950.

Both wear trousers with jackets and flat shoes and carry satchels. The woman on the left has distinctive dark, arched eyebrows framed by a fringe and loose tresses of hair. Her cool, knowing look is starkly different from that of her companion, who appears to giggle. They approach a waiting street photographer, directing their attention to the camera. The shutter clicks. After this encounter, the photographer would have offered them a card with an invitation to view – and purchase – the picture. One of the women might have taken the card, or maybe not. We do not know if this image was seen by either of the subjects, or even if it was printed. The negative survives in a collection of 127 rolls of processed film containing almost 5000 street photographs taken by a long since closed business named Ikon Studio.

Seventy years later, this digitised negative was posted in an online photo gallery by Sydney Living Museums and almost immediately the woman with the striking face was identified as Vali Myers (1930–2003), a Melbourne woman who achieved international celebrity in the 1950s and 60s as a dancer, artist, bohemian and muse. The woman photographed with Vali remains unidentified.

Vali Myers was not quite 20 years old when the photo was taken in June or July 1950, but she was already a leading dancer for the Melbourne Modern Ballet Company, performing at Melbourne’s Union Theatre, Town Hall and Assembly Hall. Although she had trouble remembering dance steps (to the horror of her teachers), her technique was described as exceptional, and her natural talent and personal flair allowed her to improvise expertly.1 Having proven herself as a professional dancer locally, she wished to pursue a career in Paris.

The Ikon Studio photograph was taken just before Myers left Australia, but little is known of her visit to Sydney on the eve of her departure. We know that she stayed at the Port Jackson Hotel in The Rocks; many years later, in 1969, she completed an artwork titled Death in Port Jackson Hotel. The handwritten text accompanying this work is perhaps indicative of her mindset during her final weeks in Australia: ‘This drawing which took me 2 years, is the suicide of a 19 year old girl, but also a rebirth, a flaming one’2

Myers left Australia on the RMS Maloja, perhaps boarding the ship in Sydney on 22 July or embarking from Melbourne a few days later. On the evening of 25 July, Vali’s friends Leonie Barr, Margaret Readion and Billie Robinson waved goodbye as the passenger liner pulled away from the docks at Port Melbourne,3 and she was on her way. Vali turned 20 on 2 August, and a few days later the ship crossed the equator.4 On the ship she met other travelling dancers, including Ananda Shivaram and Janaki Devi, renowned practitioners of the classical Indian dance form Kathakali. They were returning to India from an Australian tour. Also on board were ABC ‘showman’ Max Green and variety stars The Ganjou Brothers and Juanita, adagio dancers travelling to London.

Myers led a creative, full and unconventional life in Paris, Italy, London and New York, and eventually returned to Australia in 1993. In 1995 she established a studio gallery in the Nicholas Building on Swanston Street, Melbourne, where she continued to make and show art until her death in 2003. The work and her legacy are memorialised and celebrated by the Vali Myers Art Gallery Trust.

The Ikon Studio street photograph of Vali Myers is a chance discovery, a casual, candid image, but one that is richly evocative of her unorthodox life and style. The two women in the photograph would not look out of place strolling down Martin Place today, but their fashion choices stand out strongly when compared to the other Ikon Studio photographs from the time. Women who appear on the same roll of film wear waisted coats, patterned dresses, headwear decorated with flowers or feathers, knitted gloves, fur stoles, printed scarves and high-heeled shoes – not trousers and flat shoes.

The monochromatic photograph can’t convey a sense of Vali’s mane of natural fiery red hair or her clear blue eyes. Her flat shoes appear worn, and her distinctive poloneck jumper, wide-legged trousers and oversized coat may have been as much a style choice as a financial one. A description of Vali’s life after arriving in Paris – and her wardrobe – was published by People magazine on 31 January 1951. As she explained, Vali had left her homeland partly to pursue a dancing career, and partly to escape conventional and conservative Australia. Of her threadbare outfit, she told the journalist: ‘They were about the only clothes I had because during my dancing studies I had no money to buy others … I became attached to them and still wear them in Paris, where they are appreciated more and people don’t look at me unkindly … It was unbearable [in Australia] to feel people’s eyes drilling into me and hearing nasty things whispered about me as I walked past. I did not flee from Australia, really, but I wanted to find some other part of the world where I could lead a more undisturbed life’.5

The ‘ancient black satchel’ Vali carries in the Ikon Studio photograph was the young artist’s capsule of creativity and biography. It contained poems she wrote, her sketches and drawings, and probably the intricately illustrated and annotated diaries she kept for many years, along with photographs of her as a model.6

This previously unidentified street photograph brings to life an otherwise unseen moment and provides a fresh window into the Vali Myers story, with new insights. Vali’s confident gaze before the photographer’s lens and nonconformist attire indicate her independence even as a teenager.

Acknowledgments

With many thanks to Anne Zahalka, whose community of artists and creative friends led to the identification of the photograph. Thanks also to Ruth Cullen for sharing her insights and collection of rare books relating to Myers, and to Nicole Karidis and the Vali Myers Art Gallery Trust for sharing knowledge and the images that accompany this story.

Notes

- ‘Young dancer’s poetic grace’, The Age, 7 November 1949, p4.

- Vali Myers, Drawings 1949–’79, Open House, London, 1980, p58.

- ‘Some leave our shores – others return to stay’, The Argus, 26 July 1950, p32.

- ‘Radio – from the equator to the chessboard’, Radio Call, 24 August 1950, p24.

- ‘Australian in Paris’, People, 31 January 1951, pp8–9.

- Ibid. The Vali Myers Art Gallery Trust website includes information about the diaries Vali Myers kept.

Related

Snapped! The Ikon Studio street photographer at work

A remarkable acquisition of 5000 street snaps provides a lively and revealing record of one Sydney street in 1950 and offers a rare glimpse through the street photographer’s lens

Published on

Photography stories

Browse all

Glass-plate photography

The collection of glass-plate negatives held in the State Archives and Justice & Police Museum are endlessly fascinating and revealing

Unexpected views

Over the decades, photographers have captured unexpected glimpses of the Mint’s history

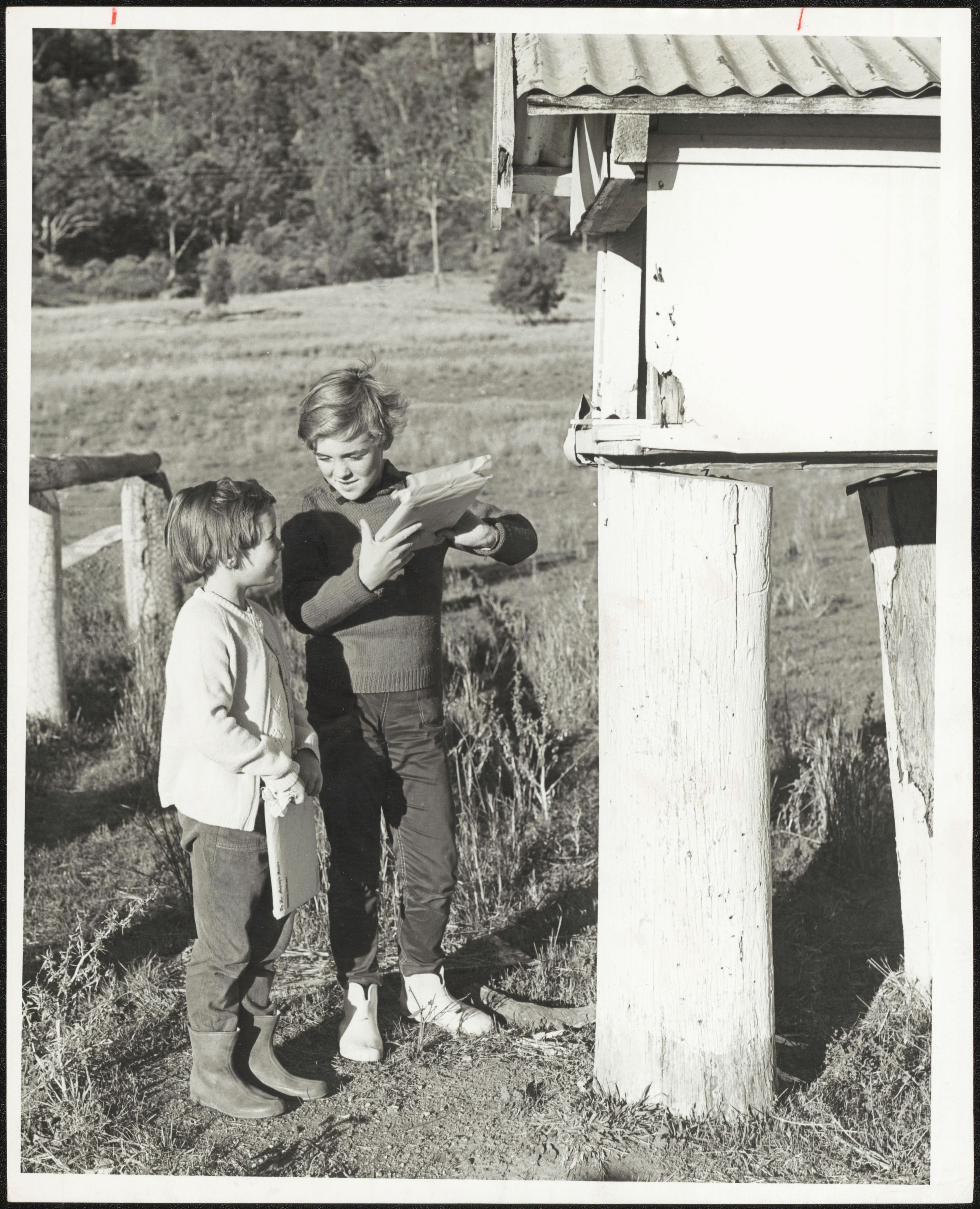

NSW Correspondence School

These photos show the NSW State Correspondence School, Blackfriars. It began in early 1916 for children living in remote and country areas

Underworld

Behind the scenes: How to read a ‘special’

Around the world, police forces followed established conventions when taking mugshots. But Sydney police in the 1920s did things differently