Norman Matthew Pearce

1881–1916

Rouse Hill House contains a number of objects that reveal the close relationships between the families associated with the house and the Pearce family, particularly Norman Pearce and his fiancée, Kathleen Rouse.

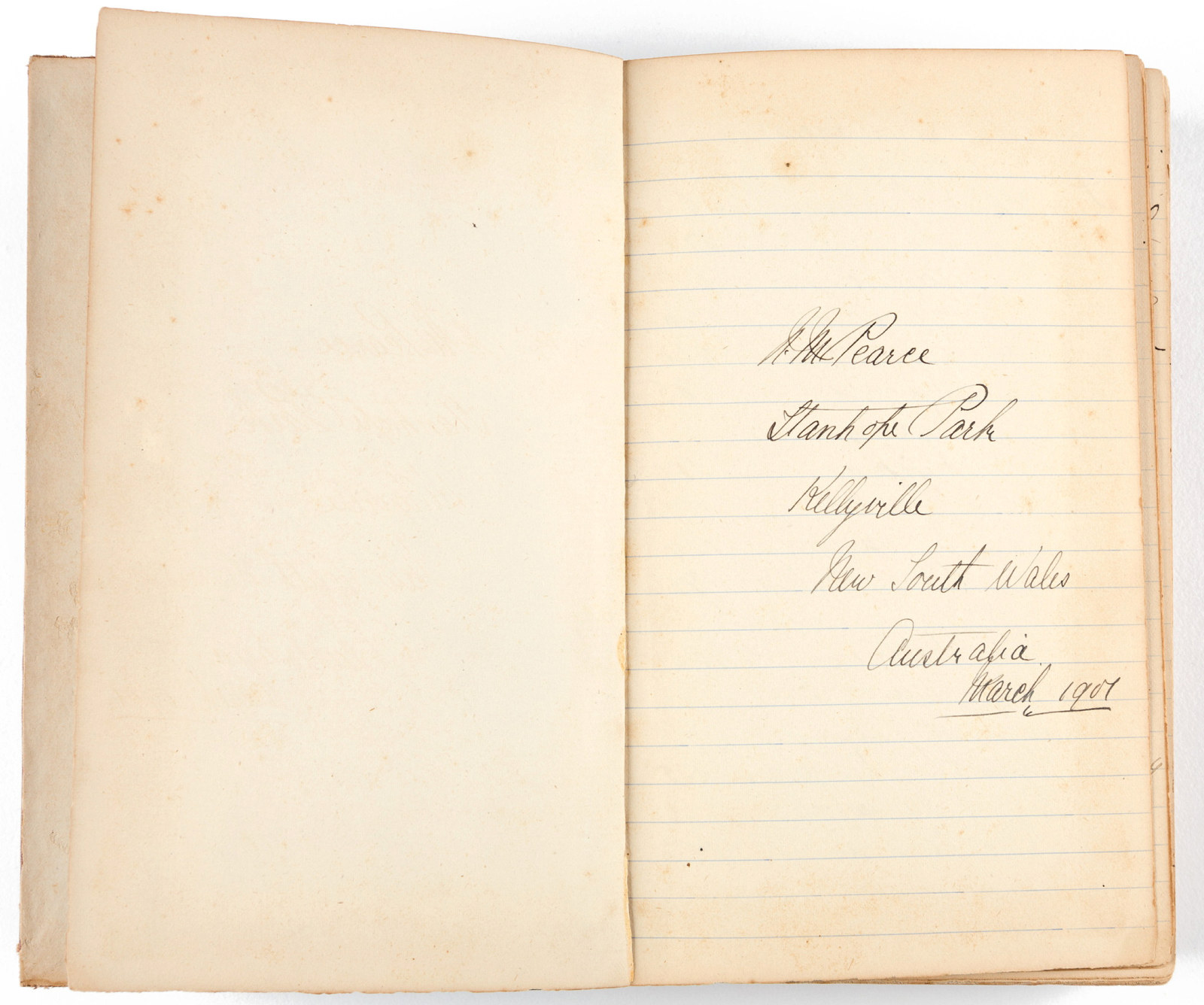

Matthew Pearce arrived in Australia in 1794 and received a land grant on what is now the Old Windsor Road the following year. A century later his descendants lived on several properties in the district, where some remain to this day. Matthew’s great-grandson Norman Matthew Pearce, the eldest child and only son of orchardist and grazier Matthew Squire Pearce and his wife, Alice Rosanna Pearce, nee Jenner, was born on his father’s property, Stanhope Park, Kellyville, on 6 January 1881.

After leaving The King’s School, Parramatta, Norman joined the Parramatta Squadron of the NSW Regiment of Lancers and was described as ‘a most promising swordsman’.1 Norman volunteered to serve in South Africa as soon as he turned 20, the minimum age for recruits. Preference was given to trained men who were ‘good shots and good riders’.2 To record this new chapter in his life Norman started a journal, commencing on 28 February 1901, the day he received his commission as second lieutenant in the 3rd Regiment of NSW Mounted Rifles. His diary account of preparations for and the voyage to South Africa is preceded by a table of distances, emphasising just how far he was to travel from his home. With his regiment camped at the old Paddington Rifle Range awaiting orders, Norman noted important milestones: receiving £35 to get his outfit, the Governor General reviewing the troops in Centennial Park, and a visit to camp by his mother, aunt and sisters, ‘bringing my revolver, glasses; and brushes’.

On 21 March Norman’s squadron embarked with much fanfare on the British Princess. The 3rd NSW Mounted Rifles served in the eastern Transvaal and Orange Free State under the command of Colonel M F Rimington of the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, participating in a number of engagements including the Harrismith ‘drive’ in February 1902, which resulted in the capture of 251 Boer prisoners, 26,000 head of cattle and 2000 horses. By now the war had entered a guerilla phase, characterised by long rides, often at night, dawn raids and skirmishes.

In a letter to his old commanding officer in the Lancers, Norman stated that his column had been doing plenty of night marching, and proudly reported that the Lancers were ‘the best-known men in South Africa’ of any colonial regiment, ‘and you have only to mention that you are a New South Wales Lancer or were one, and the people can’t make too much of you’.3 He made no mention of the harsh conditions being endured – more members of the Australian contingents died of disease than in action or from wounds sustained in battle.

Peace was declared in May 1902, and Norman departed for Australia on the Orient on 11 July. In October he was one of a number of returned soldiers welcomed home by the Parramatta Squadron of Lancers at a smoke social. By the end of the year his service in South Africa had earned him the rank of honorary second lieutenant in the Commonwealth military forces.

The Pearce family were close friends of the Rouses and Terrys. They were all active in the local community, working together at church fundraisers, and shared many common interests. Norman’s youngest sister, Mary, was musical, teaching pianoforte using her qualifications from the Royal Academy of Music and the London College of Music. Matthew, a noted breeder and judge of horses, sat on the Hawkesbury Race Club committee with George Terry, and Norman competed at local shows with George. Kathleen Rouse, the second daughter of Edwin Stephen and Bessie Rouse, attended dances at Parramatta with the Pearce children, and, as members of the Rouse Hill Tennis Club, she and Norman even appeared in a farce entitled ‘Turned up’. At some stage the couple became engaged.

Early in 1911 Matthew underwent a serious operation, and Stanhope Park was unsuccessfully put up for auction. Although readvertised for sale, it remained in the family and by 1914 Norman was managing the property while maintaining his interest in horses, breeding thoroughbred yearlings. However, with the outbreak of war he volunteered for service once more. After enlisting on 22 September 1914, he spent the next three months based at Liverpool and Holsworthy camps. Said to be the first at Kellyville to volunteer, he was given a send-off by the local Red Cross branch. As guest of honour at a concert in Kellyville in aid of the Children’s Hospital, Norman was presented with a wristlet watch and a cheque for over £20. With his fellow officers he also attended the conversazione and presentation at Parramatta Town Hall for their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Cox CB, under whom Norman had served in South Africa. On 21 December he embarked on the transport Suevic as a second lieutenant in the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, 6th Light Horse Regiment. Even as Norman sailed for the front, his family were making their own contribution towards the war effort in the newly formed Rouse Hill–Kellyville Red Cross, with Mary Pearce as inaugural honorary treasury.

Arriving in Egypt at the beginning of February 1915, his regiment spent three months camped at Maadi near Cairo. Despite training as a mounted force, their first experience under enemy fire was on foot. In mid-May the 6th embarked for the Gallipoli peninsula, landing at Anzac Cove under shrapnel and sniper fire. Here Norman, now a lieutenant, was to spend the next six months. However, towards the end of November he was admitted to hospital, just weeks before his regiment was evacuated to Egypt. Conditions at Gallipoli, where good oral hygiene was difficult to maintain and dental treatment basic and hard to come by, had aggravated existing problems with his teeth, and pyorrhoea alveolaris (chronic periodontitis), a purulent inflammation of the gums, had set in.

Norman was transferred to Malta, where a number of hospitals and convalescent facilities had been established to cope with the growing numbers of wounded from Gallipoli, complemented by a range of recreational services provided by voluntary organisations. Among photographs he sent to Kathleen are scenes from around the island, all carefully identified on the back, taking special note of particular points of interest. His photographs of Gallipoli, Malta and Egypt display a lively curiosity in not only army life and his fellow soldiers, but also the local countryside and people. Opportunities for sightseeing are revealed in photographs taken by or of Norman and in the lists of his personal effects returned to his family, which include such items as Maltese lace and two Egyptian scarabs.

Norman rejoined his regiment at Maadi on 13 January 1916 and once again settled into the routine of camp life. In late February, the 6th moved east to Serapeum on the Suez Canal and continued their training. However, in mid-May a punishing desert march in furnace-like heat over seemingly mountainous sand dunes with scant, brackish water proved too much for some of the regiment. Horses and men collapsed en route. Norman, one of a number of officers and men suffering from sunstroke and/or heat exhaustion, spent the remainder of the month in hospital.

On 19 July 1916 Norman was promoted to captain, a rank he was to enjoy only briefly. Just ten days later he was dead. On 29 July, while in charge of a listening post established to ascertain enemy movements overnight, Norman was shot at close range by a sniper on a ridge overlooking Hamisah. The three men under his command were forced to work their way back to camp via a circuitous route behind enemy lines. A private in Norman’s regiment recorded his demise in his diary with a somewhat backhanded compliment:

Poor old Norman Pearce was an unassuming Officer with very little Personality, but His Heart was stout & true. He accepted His Duties willingly & in the hour of Danger never flinching to do His part. Being one of the Senior Officers of this Regiment, work was given into His charge which needed nerve & endurance, & He rose to the occasion each time, & did it well.4

Norman was buried at Bir Et Maler above the Wellington Mounted Rifles Camp, his grave marked by a simple white wooden cross. A photograph taken soon afterwards by War Chest Commissioner W F A Larcombe was reproduced in The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate in January 1917 and periodically again over the years as the newspaper reflected on the district’s contribution to the war effort. It was probably in Norman’s memory that his mother, Alice, hosted the Kellyville–Rouse Hill Peace picnic at Stanhope Park in August 1919, and Mary handed out a shilling to each child. In May 1920 the Blacktown War Memorial was unveiled, with Norman’s name at the head of the long list of local ‘heroes who paid the supreme sacrifice’. His name was also inscribed on the Kellyville Roll of Honour at the public school, which had been unveiled in November 1917, and the Kellyville Honour Roll. The latter, unveiled in 1926, was in the Soldiers’ Memorial Hall, opened two years previously. Ilma Pearce had sat on the committee elected to erect the hall in which her brother was memorialised.

In the months and years following his death, Norman’s parents took delivery of a sad procession of their only son’s belongings and remembrances of his service. The bulk of his possessions arrived in January 1917. Among the uniforms, horse rugs, rifles and more personal items such as letters, his watch and toothbrush were other articles which perhaps give an insight into Norman’s character. Over 30 books were returned, as well as dumbbells, a tennis racquet, white linen suit, fancy waistcoat and serviette ring. It was almost a year after his death that Norman’s identity disc was finally sent home, by which time his mother ‘had quite given up all hope of ever getting it’. The booklet Where the Australians rest, his Memorial Scroll, medals, Memorial Plaque and photographs of his grave were all gradually dispatched.5

‘Mrs. Pearce was the last of the family’6

In just over a decade, this branch of the Pearce family was extinguished. Matthew Squire Pearce died after a long illness just six months after his son, in February 1917. In fact, when his wife had received a cable with news of Norman’s admission to hospital in Malta, Matthew had been too ill to even be told. By the time his family were notified in 1925 that his remains had been reinterred, his immediate family had dwindled again. Ilma died in December 1924, and Mary in October 1926. One year later Alice Pearce died, having outlived not only her husband, but all of her children. The funerals of all three women took place at Christ Church, Rouse Hill, where the family is commemorated in stained-glass windows. The contents of Stanhope Park were auctioned off, and the following year the property itself was put up for sale.

Today Norman lies in Kantara War Memorial Cemetery not far from a member of the Rouse family, another 6th Light Horseman. Lieutenant Reginald (Tim) Black MC (1886–1917), son of the Hon Reginald James Black MLC and Eleanor (Ellie) Black, nee Rouse, and great-grandson of Richard Rouse, had survived Gallipoli only to die in August 1917 of wounds received near Beersheba. Like Norman, Tim’s remains had been relocated – twice – from the military cemetery at Rafa, where he died, and then El Arish Military Cemetery, where he had been reinterred in 1919.

Footnotes

- The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 29 December 1900, p12.

- P L Murray (comp & ed), Official records of the Australian Military Contingents to the war in South Africa, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1911, p123.

- The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 November 1901, p10.

- Henry Frederick Wallace Tucker diary, 1 January–31 December 1916, p121. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW: MLMSS 1013/Item 2.

- National Archives of Australia: Australian Imperial Force, Base Records Office; NAA: B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914–1920; PEARCE NORMAN MATTHEW.

- The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 21 October 1927, p6.

More stories

On This Day

17 Dec 1915 - 'Waratah' recruitment march

On 17 December 1915 the "Waratah" recruitment march arrived in Sydney

WW1

A dubious defence

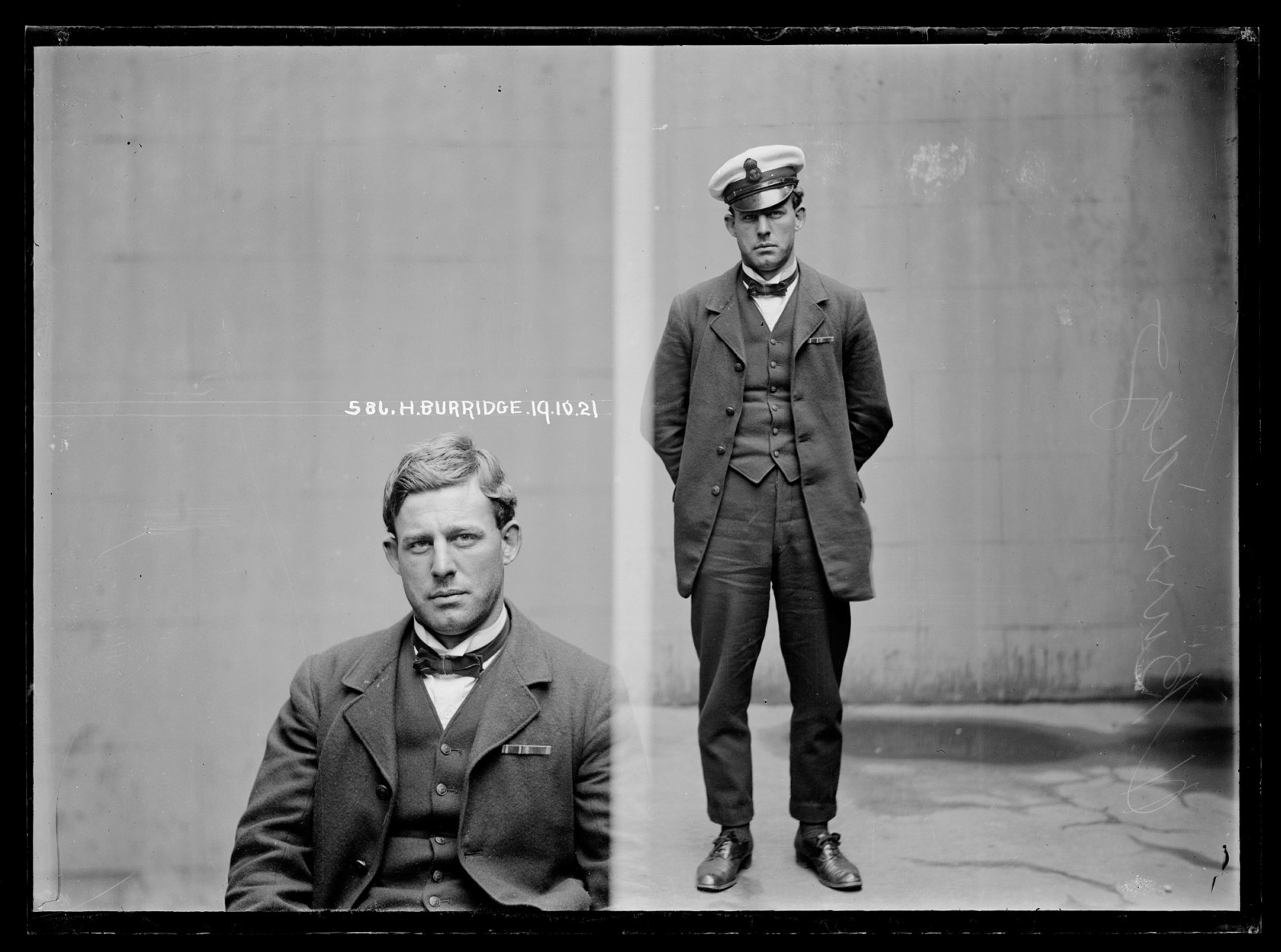

On 19 October 1921 Herbert Burridge was listed in the New South Wales Police Gazette as a deserter from HMAS Cerberus

WW1

A patriotic fundraising memento

This tiny celluloid doll, just 10 centimetres in height and clothed in panels of ribbon, is showing her age

Published on