Sydney Mint honour roll

The Sydney Mint honour roll hangs in the southern stair hall of the former Royal Mint building on Macquarie Street.

It carries the names of seven men, entered in order of the date on which they enlisted in the 1st Australian Infantry Force (AIF) for service in the ‘Great War’. The men were Charles William Miller (1886–1958), Frederick Sydney Hoptroff (1896–1956), Arthur McPhail Kilgour (1896–1941), Edgar King Upton (1894–1958), Oliver Richard Whiting (1897–1917), Theophilus Robert Bowmaker (1877–1963) and John Stanislaus Gilchrist (1899–1989). The roll itself gives neither full names nor dates but notes that Miller, Kilgour and Bowmaker were wounded and that Whiting was killed in action.

An industrial workplace

At the outbreak of war, the Sydney Mint was a small industrial workplace with a workforce comprising 18 salaried staff – the Deputy Master, a superintendent, assayers, clerks and foremen – and 24 workmen on wages. The workmen were graded as first, second or third class and worked either in the melting room or the coining factory. Six of the Mint men who enlisted in the AIF were third-class workmen, earning between five and eight shillings per day. They were aged between 15 and 17 when they started work at the Mint, and all except Charles Miller were 18 or 19 years old when they enlisted – although three of them claimed to be older on their attestation papers. Jack Gilchrist, the youngest, was the last to enlist, doing so with the consent of his parents in May 1918. His father, Thomas Charles Gilchrist, was Second Foreman of the melting room. He had been temporarily transferred to the Ottawa Mint for six months in 1916 to fill a skills gap created by the enlistment of Canadian Mint men. Son Jack left Australia in October 1918, and by the time he landed in England before going on to France, the fighting was coming to an end.

Charles Miller was the first to join up, enlisting just two months after the hostilities began. Having been at the Mint since 1904, he was an experienced industrial worker earning eight shillings a day working as an assayer in the coining factory. As a soldier with the rank of private, Miller was paid six shillings per day, and the army automatically withheld one shilling, the accrued total to be collected at the completion of his service. But as an employee of the Royal Mint his job was protected and any difference between his pre-service pay and army pay was made up by the Mint.

Miller was the only one of the Mint men to serve at Gallipoli. He was attached to a Field Artillery Brigade, working under pressure and managing heavy weapons in tight, cramped conditions. Having arrived in the army already familiar with routine and training in heavy machinery, he was somewhat familiar with the required retraining to operate new pieces of heavy machinery. Miller went on to the Western Front, where he served out the remainder of the war, despite being wounded in April 1917. After the armistice he returned to the Sydney Mint in April 1919. He had been promoted in the normal incremental way during his absence and returned as a second-class workman on ten shillings a day.

Theo Bowmaker was the only white-collar employee on the Sydney Mint honour roll. He was a graduate of the University of Sydney and had started work at the Mint on 1 January 1896 as a junior clerk. By the time he enlisted in March 1916, he was earning around £300 per annum. He was nearly 39 when he farewelled his wife and travelled to Goulburn to sign up, lowering his age to 33 in the process. He spent two months in Goulburn Depot Camp, was promoted to corporal (and later acting sergeant), then headed to Sydney midway through the year to attend the Non-Commissioned Officers’ School. Between July and October he was based at Liverpool, where he learned entrenching and bomb-throwing skills before embarking for England in October 1916. He remained in England until September 1917 and continued to train in the ways of war, becoming proficient on the Lewis gun, a light, mobile machine gun that was as effective in the field as 50 riflemen. On 13 September 1917 he finally proceeded to France and was taken into the 56th Battalion, which entered battle on 26 September at Polygon Wood, near Ypres in Belgium.

The environment of Polygon Wood was incredibly hostile. Amid a mass of smoke and shellfire, troops from the 56th were shot by their own men in crossfires and were hit by their own artillery on a number of occasions. As the day’s action progressed, the soldiers fulfilled a range of roles. Lewis gunners moved to key vantage points, and as a trained gunner Bowmaker may have been deployed as such. Forward posts were consolidated, patrols sent out to watch for inevitable counterattacks and the battalion’s ‘line’ was straightened, withdrawn and repositioned a number of times. The men on the ground were watched over by men in the air, and artillery barrages were called in when enemy troop movements were spotted.

By the close of day the casualty assessment for the 56th Battalion was nine officers and 100 men – one of whom was Bowmaker. He had been seriously wounded, sustaining a gunshot wound to the back of his leg. It shredded his posterior tibial artery and invalidated him out of the front line for good. Having trained for months to become a skilled soldier, he was a valuable asset among many thousands thrown into the offensive. He was then swiftly removed from the roll of functional men available to the army on his first day of action. He returned to Australia before the end of the war and went back to his desk job at the Sydney Mint on 30 September 1918. His foot was so badly damaged that it would likely not have withstood the rigours of manual labour.

Arthur Kilgour, the other man who is listed on the honour roll as wounded, returned to the factory floor in March 1920.

Unveiling the memorial

The Sydney Mint honour roll was designed in a simple style, using the language of classical architecture, with the list of names framed by Doric columns supporting an entablature carrying a shield with the painted coat of arms of the Royal Mint. The shield is a reminder that most of the employees of the Sydney branch of the Royal Mint were imperial civil servants. The men whose names are on the board all had their appointments authorised and gazetted in London.

All but Oliver Whiting were back at work at the Mint when the memorial was unveiled by the Governor of NSW Sir Walter Davidson on 6 October 1920. So was a Mint watchman named Daniel Clifford. He had served in the Royal Australian Navy from 1916 to 1919 but his name is not on the board. Appointed locally, he was not part of the ‘establishment’ of the Mint. One other ‘missing’ name is that of assistant assayer Raymond Stoddart. He had tried to enlist but was rejected for foreign service on health grounds. Instead he took leave from the Mint to serve as a captain in the Home Defence Forces. He died at the age of 36 on 21 July 1918 and his memorial is a plaque in the church of St Matthew’s, Manly, erected by ‘fellow workers and children of St Matthew’s Sunday School’.

Published on

More

WW1

Commemoration

Hear the poignant personal stories behind battlefield grave markers in Egypt, France and Gallipoli, as well as the stories behind workplace honour rolls, one of the most common, but often hidden, forms of war memorial in Australia

WW1

Home Front

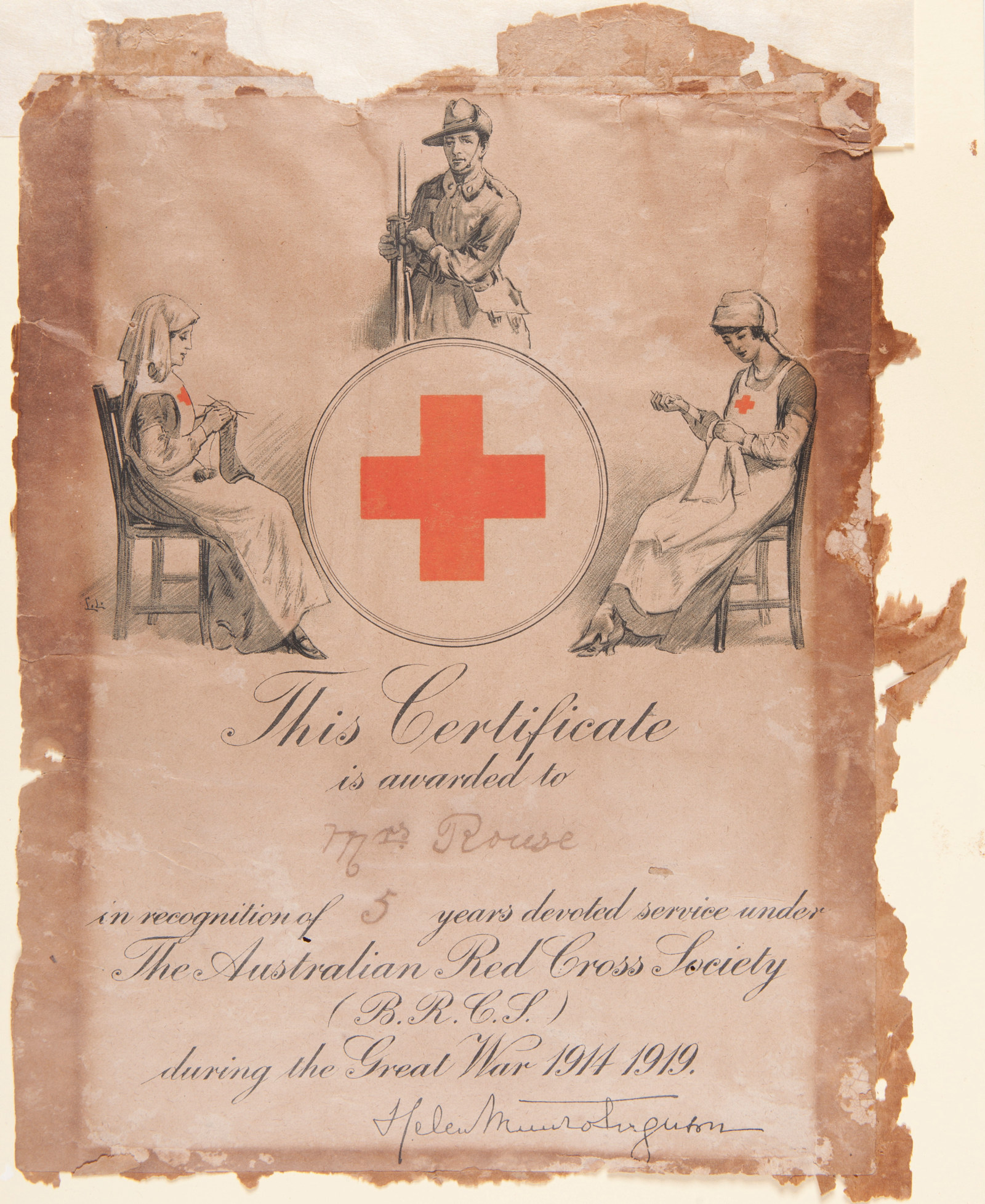

As the war stretched on, thousands of women at home in Australia supported the war effort by volunteering for patriotic fundraising activities

WW1

War Service

From the shores of Gallipoli to the sprawling Western Front, the stories told here reveal the powerful war experiences of ordinary soldiers. Some were decorated for bravery in the field, while others made the ultimate sacrifice