The Wobblies

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as the ‘Wobblies’, was a radical labour organisation founded in the United States in 1905.

The organisation was opposed to the separation of workers’ unions by crafts, committed instead to providing ‘one big union’ for all workers, including unskilled and semi-skilled workers ineligible to join established trade unions. By October 1907 the IWW had arrived in Australia with the establishment in Sydney of a club under the aegis of the Socialist Labour Party. Clubs were also established in Melbourne, in the coalmining towns of the Newcastle region, in the copper town Cobar in north-western NSW and in the tin-mining town Herberton in far north Queensland. In Sydney, male and female members of the IWW met to read, learn and debate issues at regular meetings and educationals held in the IWW rooms in Sussex Street. IWW women gave talks in the clubrooms on such subjects as motherhood, marriage and prostitution.

In 1911 an amendment to the Commonwealth Defence Act provided for compulsory military training for boys aged 12 to 18. The IWW began recruiting in earnest, and the discussion clubs became organised IWW Locals. With Britain’s declaration of war against Germany in 1914 and the Australian government’s decision to send troops to serve overseas in support of the mother country, the IWW took every opportunity to oppose the war, arguing that capitalist society was completely dependent on its working class to provide recruits for its army. The IWW generally acted in defiance of the War Precautions Act, under which censorship controls were introduced in Australia. Members openly sold literature that was deemed prejudicial to the recruitment of ‘his majesty’s forces’. By 1916, when Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes announced his intention to hold a referendum to introduce conscription, the IWW’s militant opposition to the war made its activities a key focus for police and politicians.

The NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive, held in the collection of the Justice & Police Museum, includes a box of glass plate negatives labelled ‘IWW Dope’, a reference to allegedly incendiary materials, including cotton waste and turpentine, found during police raids on IWW premises. The images were part of the police forensic evidence in 1916. Today they testify to an organised anti-IWW campaign that by the end of the war had culminated in suppression of the organisation.

The opening action in the police campaign was the arrest in September 1915 of Tom Barker, secretary of the Sydney IWW Local and editor of the organisation’s newspaper, Direct Action. Barker was arrested for printing a poster calling on workers ‘to follow their masters and stay at home’. He was found guilty of breaching the regulations of the War Precautions Act, but the conviction was overturned on appeal. Six months later he was again arrested, this time for printing a cartoon that attacked war profiteering. He was convicted and sentenced to 12 months’ jail. IWW members protested strongly against the verdict.

The ‘Sydney twelve’

In the lead-up to the conscription referendum held on 28 October 1916, NSW police were particularly diligent in prosecuting Wobblies for inflammatory and seditious speech at the gatherings that took place every Sunday in Sydney’s Domain. On 23 September, police raided the Sussex Street meeting rooms and later searched members’ homes. They confiscated a range of items, including political flyers, an artwork, and materials that could be used to start fires. Between June and September 1916 there had been a series of suspicious fires in Sydney business premises, believed by some members of the police to have been set by IWW members as part of their campaign to have Tom Barker released from prison.

Following the raids, twelve men – Charles Reeve, Thomas Glynn, Peter Larkin, John Hamilton, Bernard Bob Besant, Thomas Moore, Donald McPherson, Donald Grant, William Teen, William Beatty, Morris Joseph Fagin and John Benjamin King – were charged with conspiracy to commit arson, conspiracy to prevent the course of justice (through the campaign to release Barker), and conspiracy to cause sedition. The men, who would become known to historians as the ‘Sydney twelve’, were all found guilty of at least one offence, with some being found guilty of multiple charges. Seven men were sentenced to 15 years’ jail, four to ten years and one to five years. In 1920 an inquiry into the trial and sentencing found that six of the men had not been ‘justly or rightly’ convicted of sedition. Four others were found to have been involved in conspiracy of a seditious nature but were recommended for release. These ten were released in August 1920. The remaining two were released slightly later, although one was judged to have been rightly convicted of sedition and the other found rightly convicted of arson.

Murder in Tottenham

Within days of the arrest of the Sydney twelve, an event took place in the small town of Tottenham in central west NSW that added impetus to the political push to repress the IWW. Copper mines were the major source of employment in the area, attracting mostly unskilled labour. A Tottenham chapter of the IWW, Local no 9, had been formed in May 1915.

On 26 September 1916, Constable George Duncan set out to find an IWW member, Roland Kennedy, whom he intended to summons for offensive behaviour and obscene language. Tensions were already running high between Duncan, who had allegedly been posted to Tottenham to ‘clean up’ the town, and IWW members. He didn’t find Kennedy, but Kennedy heard that the constable was looking for him. Later that night, Kennedy, fellow Wobbly Frank Franz, both armed, and possibly a third man, who has not been identified, set out to find the constable and ‘teach him a lesson’. He was at his desk in the police station, and Kennedy and Franz shot at him through the window. Duncan died of his wounds soon after. One bullet had torn through his right lung, a second shattered two ribs. Police traced the crime back to Franz, Roland Kennedy and his brother Michael ‘Herb’ Kennedy, who were known members of the IWW. The three were charged with murder, although Herb denied any involvement. At their trial, Franz and Roland Kennedy admitted they had fired their guns but claimed they missed the officer; each claimed the other had planned the shooting. The Crown prosecutor stated that the reason for the murder was ‘the pernicious literature of the IWW.1 Both men were found guilty and sentenced to death. Herb Kennedy was found not guilty.

Duncan’s murder by IWW members, combined with the charges against the Sydney twelve, was a powerful weapon in the hands of politicians who wanted the IWW shut down. Within a week of the conclusion of the trial of the Sydney twelve, a new Unlawful Associations Bill was introduced into the federal parliament and passed in a single session. The 1916 bill declared the IWW to be an unlawful organisation but did not specify that membership of the IWW was illegal. That came with an amendment in July 1917 which specified that any person who remained a member of the IWW one month after the declaration of the amended act would be liable for six months’ imprisonment.

Eva Lynch and the Unlawful Associations Act

Following the amendment to the Unlawful Associations Act, dozens of IWW members were rounded up and prosecuted. One of these was Eva Lynch, an outspoken member of the IWW and a supporter of the Irish republican organisation Sinn Fein.

Lynch was arrested while addressing a meeting in the Sydney Domain on Sunday 16 September 1917. She was reported to have declared that she was training ‘girl speakers’ to attend the Sunday meetings and keep the movement alive until their men came out of jail. She appeared in court wearing a coat with a red flag embroidered on it and entered a plea of not guilty, but was convicted and sentenced to four months’ hard labour – reduced from the statutory six months because she was the first woman to be charged under the Act.

Prosecutions under the Unlawful Associations Act were combined with deportations of non-Australian-born members of the IWW. Together these operations succeeded in effectively suppressing the organisation in Australia.

Footnote

1. ‘Tottenham murder’, The Maitland Weekly Mercury, 21 October 1916, p5.

Published on

More

On This Day

17 Dec 1915 - 'Waratah' recruitment march

On 17 December 1915 the "Waratah" recruitment march arrived in Sydney

WW1

A dubious defence

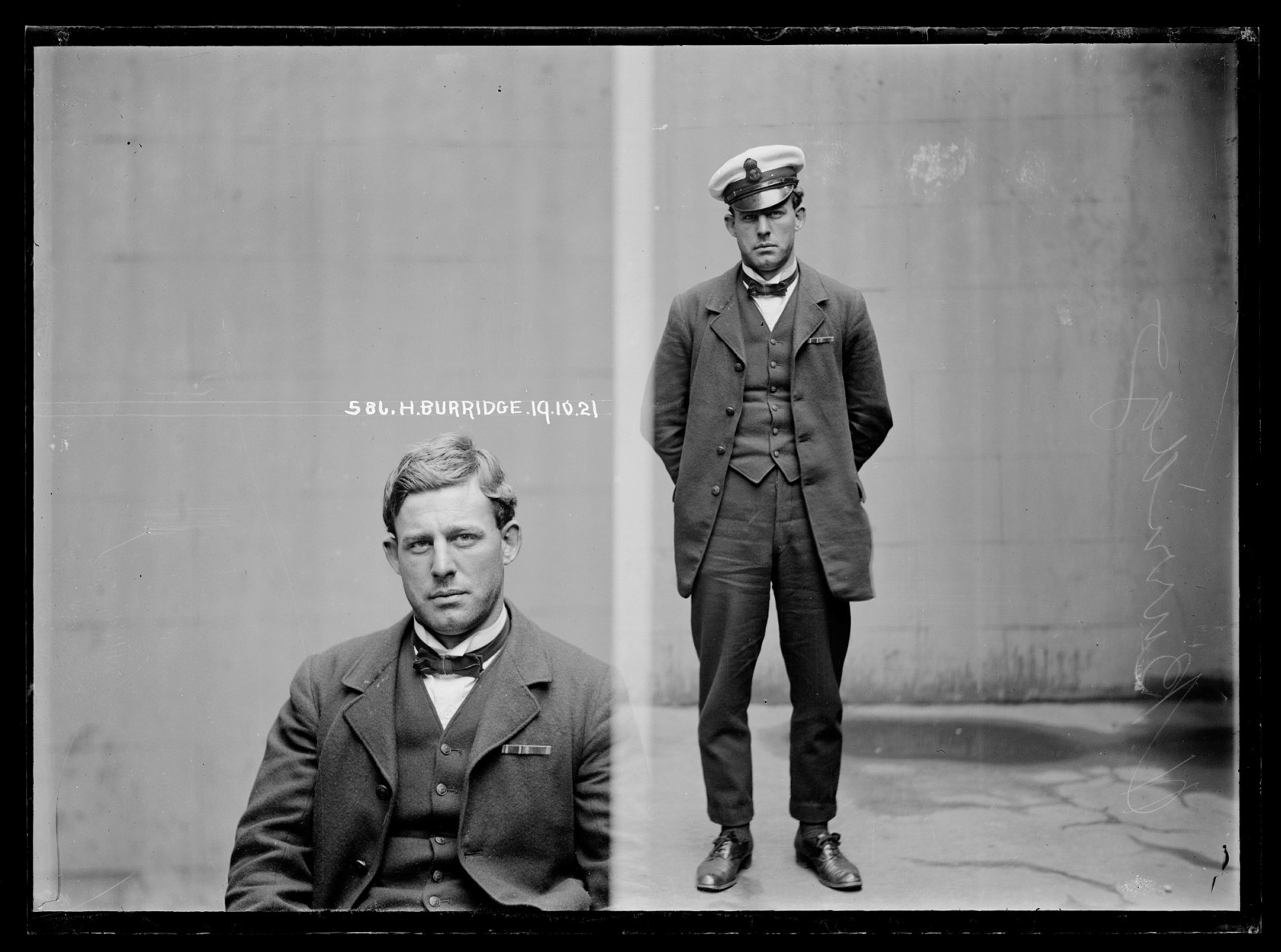

On 19 October 1921 Herbert Burridge was listed in the New South Wales Police Gazette as a deserter from HMAS Cerberus

WW1

A patriotic fundraising memento

This tiny celluloid doll, just 10 centimetres in height and clothed in panels of ribbon, is showing her age