‘Here’s luck to the aniseed!’: The Sydney Hunt Club

Seen throughout Rouse Hill House are compelling reminders of how important horses were to the Rouse and Terry families. One eye-catching image evokes a visit by the Sydney Hunt Club – and a day that was ‘truly English’.

In the vestibule at Rouse Hill House, a large framed photograph labelled ‘A group after the hunt, Rouse Hill, 18 July 1895’ is a favourite among visitors and staff alike. Those depicted were members and associates of the Sydney Hunt Club, an institution of Sydney’s society. They were spending an exciting day on horseback in the manner of an English fox hunt.

Third from the right in the front row is Rouse Hill’s then owner, the genial Edwin Stephen Rouse. Behind him are his daughters, Nina sitting in the centre of the row (newly married to the moustachioed George Terry standing behind her, holding his cap) and Kathleen in the striped dress, and between them their mother, Bessie. Standing to the right of George is the group’s best-known member, the clean-shaven ‘bush poet’ Andrew Paterson, better known as ‘Banjo’. The Evening News wrote that the riders ‘formed a striking picture of a truly English sport set on a typical Australian frame’.1

The Sydney Hunt

As the colony pushed outwards through the 19th century, hunting with guns, dogs and horses led to the destruction of many traditional food sources for Aboriginal people. Kangaroos and emus became a rare sight to the east of the Blue Mountains. With the expansion of European farming, many native animal species were even classified as ‘vermin’, and their destruction not simply encouraged but legislated. By the end of the century, animal protection legislation was being introduced, though it was often ineffectual.

Hunting and riding had long been pastimes of the colonial well-to-do. In 1825, the ‘jovial landholders at Bathurst … in imitation of their worthy old English compeers’2 founded the Bathurst Hunt, dedicated to hunting and eradicating the ‘Native Dog’ – the dingo. Closer to Sydney, the Cumberland Hunt, founded in 1838, ran cross-country rides and high-stakes races. Foxes were introduced to mainland Australia for hunting in the 1850s and rapidly became a pest species. The need for their control, as much as the desired patriotic ‘Englishness’ of fox-hunting, was used as a major argument in support of formal hunting.

The first Sydney Hunt Club was founded in August 1872, with the annual subscription a hefty ten guineas. Despite the ‘hunt’ in its name, club gatherings typically included races, hurdle rides and cross-country steeplechases. Only four years later, the club crashed and the hounds were auctioned. In 1887 the economically overstretched Cumberland Hunt also dissolved; members of both clubs re-formed as a new Sydney Hunt.

… the horses are unboxed, and saddles put on, after which a move is made for the scene of the action … whence the runner has started with his appalling burden of red herring and aniseed.

‘Hunting in New South Wales’, The Lone Hand, 2 September 1907

The Sydney Hunt: take 2

The new iteration of the club contained prominent members of Sydney society, including the governor, Charles Carrington, and newspapers closely followed its activity. Members typically hosted club events at their estates. At Box Hill in Sydney’s north-west the hosts were George and Nina Terry. George was an accomplished rider, both racing and cross-country, and – like his uncle Edward Terry MLA – served as the Club’s Master of the Hunt, leading the rides and responsible for the hounds. George even maintained a private racecourse – a feature of the high life that would eventually cost him dearly.

As with fox-hunting in Britain, riding to hounds in NSW was a sport open to women. This was made possible by the invention around 1830 of the ‘leaping horn’, a downward-curving hook added to the side-saddle against which a rider in a skirt could brace her lower leg in a jump and stay firmly seated.

‘A very pleasant day’s sport’

The club persevered through the financial crises and crippling drought of the 1890s. The Evening News reported of the July 1895 meet at Rouse Hill that ‘a stag was [to have been] the principal object of this day’s “run” … But on the preceding evening this long suffering animal had escaped from his enclosure, and had a “run” on his own account’.3 It’s questionable whether a deer was ever actually present at club meets, or whether it was just a teaser to generate interest. Taxidermied deer heads still hanging in the Rouse Hill vestibule weren’t from local hunts but imported. They echo the decoration, heavy with hunting trophies, of contemporary Edwardian hunting lodges and houses in Scotland, and reinforce the ‘Britishness’ that was central to their owners’ identity.

What a drag!

Rather than pursuing an animal, the 1895 Rouse Hill and other club rides were a ‘drag’, where a hessian sack soaked with pungent aniseed or fish oil was carried along a planned route, laying a scent trail for the hounds to follow. This way the course was prearranged to avoid planted fields, livestock or excessive dangers, while ensuring the excitement of jumps and good vantage points for spectators. A ‘check’ – a pause where dog, horse and rider could catch their breath – was created by lifting the sack and breaking the trail. The dense Australian bush, with dangerously uneven terrain into which an animal could disappear, was one reason why a predetermined drag was a far more popular option. Regardless, accidents were common, from dislocated shoulders and broken bones to being left unconscious after a fall.

Banjo Paterson wasn’t the only ‘bush poet’ to ride with the club. Harry Harbord Morant, popularly known as ‘the Breaker’ for his horse skills, joined them in 1897–98 while living in Windsor. In a poem that evokes the energy of the ride, he wrote of his preference for the fast-paced thrill of ‘the drag’ over an actual hunt:

A Song of the Sydney Hunt

There are some who hunt the red deer, and some who chevy [i.e. chase] hare,

Fox-hunters of their straight-necked quarry brag,

But faith! this side of Jordan there are few things to compare

With racing over fences – with a drag!

Let other fellows follow other packs, in various styles;

Give us grass paddocks fenced with ‘post and rails’,

And while the hounds are running over half a dozen miles,

May we be sailing close upon their tails.

There is just one trifling detail which it’s well to look to, mate!

Ride a well-bred nag – and have him fit and well,

That over five feet timber makes a trifle of your weight,

And ‘conditioned’ fit to gallop on to h-ll.

Let the ‘currant jelly sportsman’ go a-circling after hare,

Let the ‘road men’ ride their own way after stag,

Who will may follow Reynard [i.e. a fox] – but may you and I be there,

For a steaming twenty minutes – with the drag!

Oh, here’s luck to ‘the aniseed’ that runs a beeline track!

To the fast hounds that we ride to! and the nag

That bears one safe and speedily hard on the flying pack,

When they’re running, running, running – with the drag!

Published in the Richmond and Windsor Gazette, 17 July 1897

A local critic would later retort: ‘I am glad to hear from so good an authority as Mr Morant that the main idea of the Sydney Hunt Club is a good gallop, and that its members are sufficiently humanitarian to recognise that their “riding to hounds” is “better and cleaner” than hunting a fox, a hare, or a stag; but then, without this incentive to kill, one fails to see where the sport comes in’.3

Perhaps one of the finest jumpers that ever looked through a bridle is Barney, 24 years of age, who now carries Mr George Terry, riding 14 stone, safely over the biggest fences.

‘Hunting in New South Wales’, The Lone Hand, 2 September 1907

The last ride

As the century turned, the club’s membership was greatly depleted by the Boer War, with many members leaving to fight in South Africa. The club’s remaining membership was also in natural decline, as older members were simply no longer up to hard riding. Edward Terry, a mainstay of the club, died in November 1907, and two months later, on 30 January 1908, the inevitable decision was made: the Sydney Hunt would merge with the Sydney Harrier and Riding Club to become the reborn Cumberland Hunt Club. Its first ride was held on 9 May. With a terrible symbolism, only a few days later one of the Sydney Hunt’s longstanding members, Joseph Giuliani, was thrown from his horse returning from a meet and killed, leaving a widow and ten children.

In 1921, George Terry’s years of high living finally caught up with him and, after attempting to sell assets to repay his considerable debts, he was declared bankrupt. Box Hill, with its horses, stables and racecourse, was sold. George and Nina relocated across the Windsor Road to her parents’ home, where memorabilia from the club found its way onto the walls. Today, these continue to evoke the heady days of the Sydney Hunt, when the fields of Rouse and Box Hill houses echoed to the calls of dog and rider.

Notes

‘A day with the hounds’, The Evening News, 27 July 1895.

The Australian, 10 February 1827.

‘Correspondence’, Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 1 October 1898.

Published on

Related

A Gothic Angel

In the drawing room at Rouse Hill your eye is instantly drawn to a small painting on the far wall; a figure of an angel in a shining gilt frame, acquired in the 1870s.

Keeping cool

Shading the face, fanning a fire into a blaze or cooling food, shooing away insects, conveying social status, even passing discreet romantic messages - the use of the fan goes far beyond the creation of a breeze.

WW1

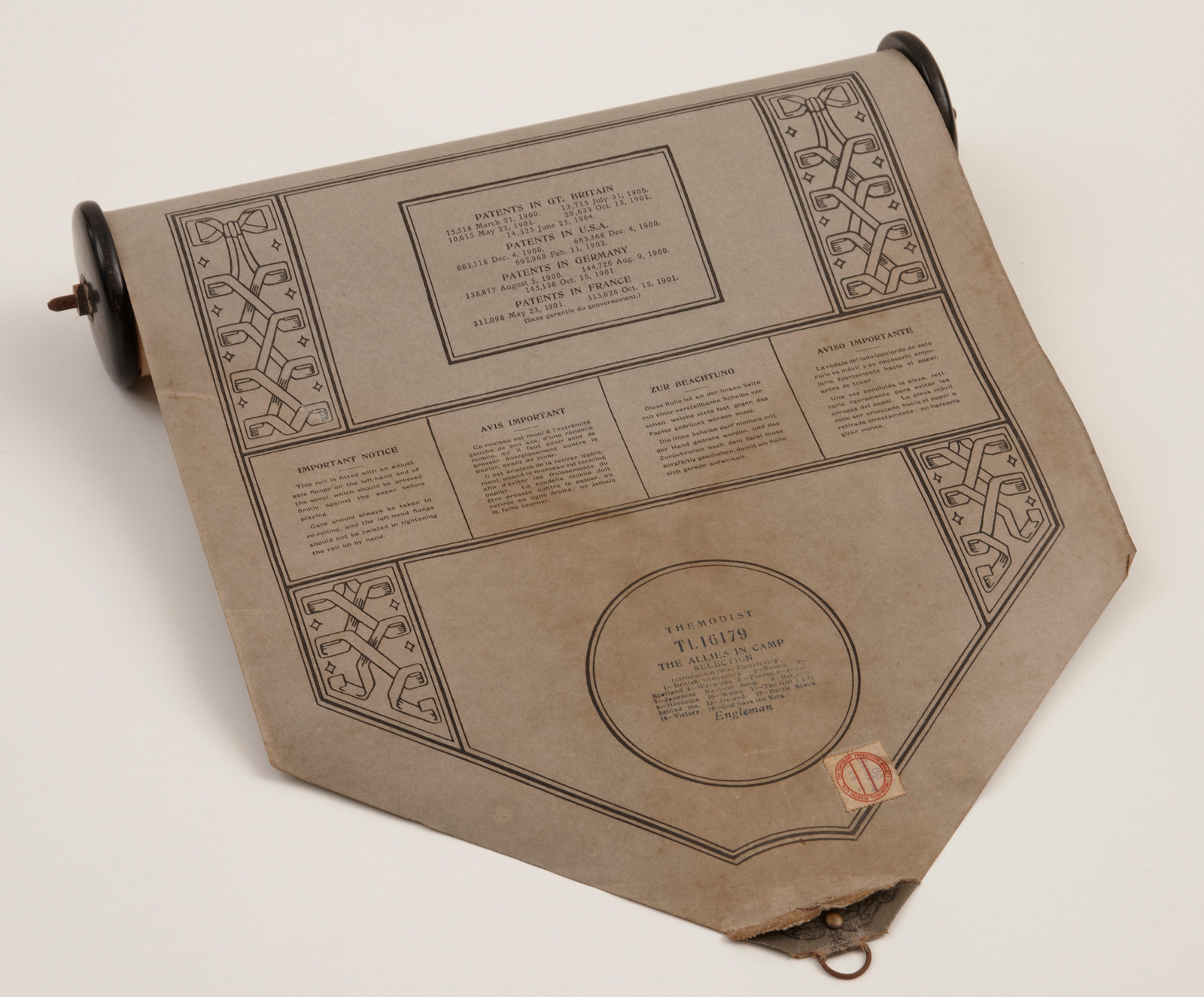

The Allies in camp music roll

Rouse Hill house boasts a fine pianola, a player piano, which came into the house just a few years before the outbreak of World War I

Baubles, brooches & beads

We wear jewellery as articles of dress and fashion and for sentimental reasons – as tokens of love, as symbols of mourning, as souvenirs of travel