‘Escapade’ at Eveleigh

On 2 August 1917, workers at Sydney’s Eveleigh railway workshops and Randwick tramway depot went on strike over the introduction of a time card system. The strike quickly spread beyond the railways and Sydney, to the wharves and coalmines, and to sugar refinery employees, timber workers, meat workers and many others.

Branding the striking workers as disloyal to the Empire, the NSW Nationalist government worked with the Farmers and Settlers’ Association and the Primary Producers’ Union to recruit thousands of ‘loyalist’ strikebreakers, accommodating them in camps at Sydney Cricket Ground and Taronga Park.

Senior students from Sydney private schools also enrolled as ‘loyalist workers’ for the six-week duration of the strike. Judging from reports in the schools’ magazines, at least some of the boys regarded the experience as a jolly ‘escapade’. The above image of a group of King’s School boys shown posed beside a railway engine daubed (or chalked?) with graffiti clearly conveys a sense of boys on an adventure. On 22 August 1917, the Sydney Mail published a photograph of an engine under repair at Eveleigh similarly ‘inscribed’ with the initials of four of Sydney’s leading private boys schools – The King’s School (TKS), Sydney Church of England Grammar School (SCEGS/SHORE), Newington College (NC), Sydney Grammar School (SGS) – and the Engineering School of Sydney University.

The boys were gung-ho and patriotic, eager to ‘do their bit’, but at least one Newington College student felt that the experience of working at Eveleigh had enabled him ‘to appreciate a workman’s feelings’, adding that ‘anyone who before had unwisely railed at unions became as good a unionist as the strikers. Only so far, of course, as it is possible for a scab to be anything good’.1 On the other hand, ‘Algernon Kerphupps’, writing in The Sydneian, suggested that in later life Sydney Grammar boys would recall their engagement with Eveleigh ‘with pride and pleasure’.2 Perhaps that was how it was remembered by Rod Terry of Box Hill and later of Rouse Hill House, former King’s School student and school friend of Phil Artlett, the boy sitting in the foreground of the photograph. The drawing-pin marks at the corners of the photograph bear witness to a time when the picture was pinned to Rod’s office wall.

For returning strikers at Eveleigh the experience was much grimmer, leaving them with bitter memories of class war. Thousands of men had been ‘dismissed by proclamation’ during the strike and when ‘re-employed’ after the return to work found themselves stripped of seniority and of superannuation entitlements. And some did not return: 2200 men had their employment records marked ‘not to be re-employed’.

Footnotes

1. The Newingtonian, September 1917, p695.

2. The Sydneian, September 1917, p27.

Published on

More

On This Day

17 Dec 1915 - 'Waratah' recruitment march

On 17 December 1915 the "Waratah" recruitment march arrived in Sydney

WW1

A dubious defence

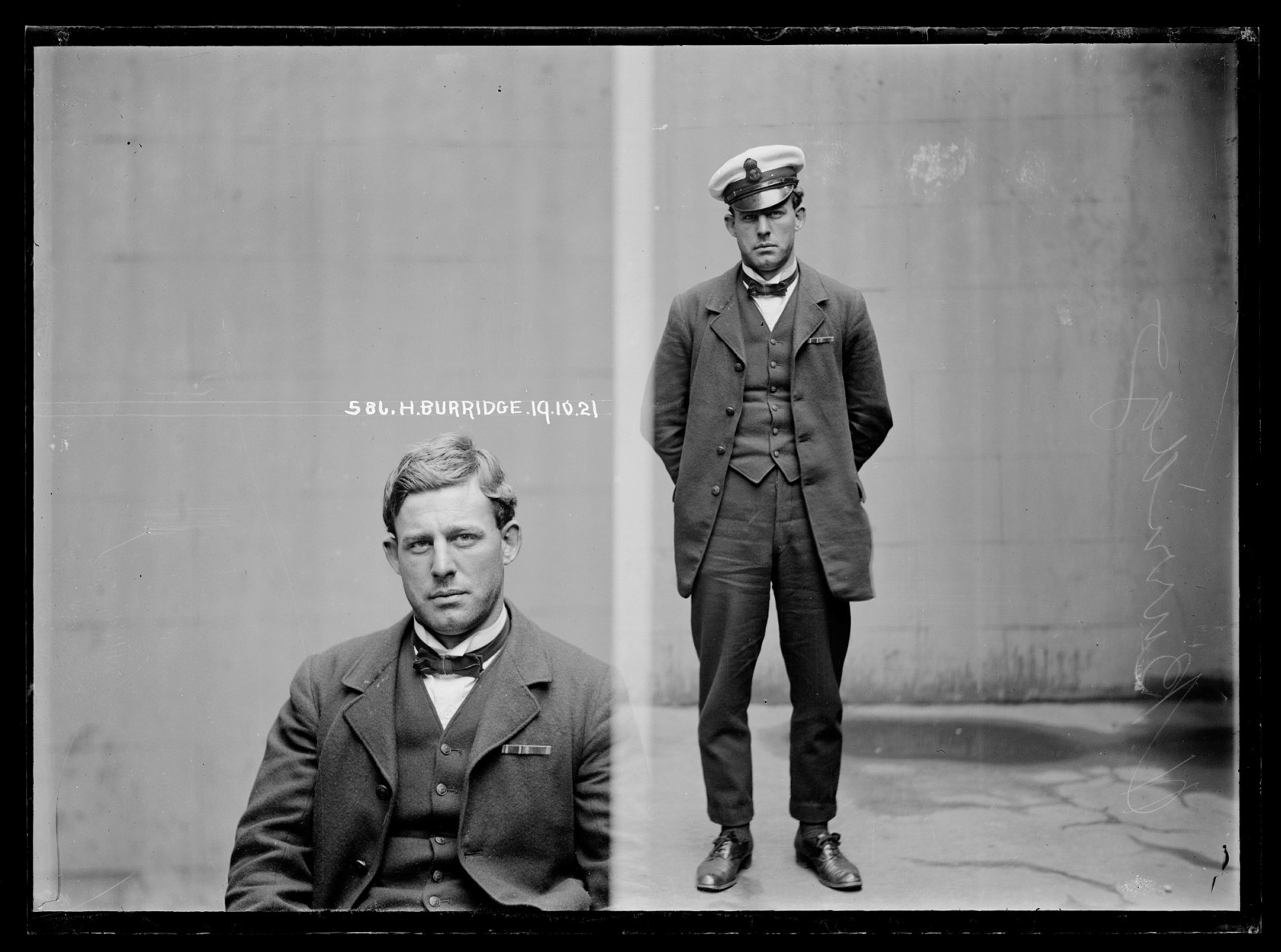

On 19 October 1921 Herbert Burridge was listed in the New South Wales Police Gazette as a deserter from HMAS Cerberus

WW1

A patriotic fundraising memento

This tiny celluloid doll, just 10 centimetres in height and clothed in panels of ribbon, is showing her age